To see a brief video clip of the 1967 "Guys and Dolls," click here.

The Chastain Ampitheatre in North Fulton Park was a WPA project and seated appropriately 6500 on stone bleachers. Its grand opening on July 19, 1944 under the auspices of the Fulton-Dekalb Horse Show Committee featured musical talent including Perry Bechtel, known as "The man with ten thousand fingers."

The Chastain Ampitheatre in North Fulton Park was a WPA project and seated appropriately 6500 on stone bleachers. Its grand opening on July 19, 1944 under the auspices of the Fulton-Dekalb Horse Show Committee featured musical talent including Perry Bechtel, known as "The man with ten thousand fingers."

No one knew quite what to do with this miniature Hollywood Bowl, so mostly it sat vacant. Located "way out" in North Fulton County, not then part of the City of Atlanta, it was not designed for theatrical purposes, merely a band shell with no wings whatsoever.

|

| Courtesy, Janice McDonald |

"Moonlight Opera" got off to a rousing start when radio and movie superstar Bob Hope sold out a pre-season one-nighter for charity. Left to right, Jerry Collona, happy bandleader Desi Arnaz, an Atlanta announcer, Hope and Vera Vague.

The New York producers poured today's equivalent of $750,000 into stage and house improvements, converting the naked band shell (left) into a proscenium stage. Improvements included the creation of wings to accept the wagons which served to move the sets and erection of masking walls to conceal them.

New York USA Designer/scenic artist Ernest Southern "could sketch, build and paint" all the opera sets from memory in his shop downtown on Atlanta's film row on Luckie Street. Each play required six sets "thirty feet high by sixty feet wide, mounted on 'trucks' which roll the set on stage."

Somehow the terribly optimistic showmen increased the seating capacity to 8,500! That's a lot of tickets, and perhaps it was unlucky to say exactly how many. The combined population of Atlanta and Fulton County was only 467,000.

The opening went well, only 575,000 left to sell.

But it was downhill from there.

The rains had killed them, and the Moonlight Opera, instead of playing out their ten-year contract, folded after four and one-half weeks. Only the Equity actors received even a portion of their pay, and after the first week, no one else got paid.

Left without a tenant, the amphitheatre reverted to occasional use, such as a square dance held in 1949 for employees of Davison's. Note the original shell lighting.

To revivify the moribund facility, Hartsfield tapped Atlanta go-getter businessman Maurice B. "Bromo" Seltzer as Municipal Theatre head.

Illustrating on a grand scale "the triumph of hope over experience" and despite scattered showers, Theatre Under the Stars presented its first show without interruption, picking up where the Moonlight Opera had left off with "Desert Song," choreography by Niggemeyer.

Bromo's first season wisely included productions of Broadway musicals including "Hit the Deck," "Kiss Me Kate," and "Carousel." The latter starred Eric Mattson as Mister Snow, playing the role that he had created in New York in the original. To Atlanta, this man was a Star.

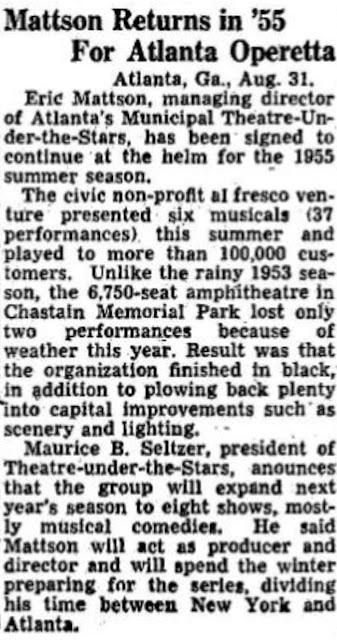

Bromo hired Mattson as Producer/Director of the series, commencing in 1954, as described in Variety, and this time around the chorus as well as the principals would be under Equity contract. Mattson, who would continue to spend winters in New York, auditioned singers by ear only, screening them off so he couldn't be led astray by good looks.

More improvements were made to the Chastain park stage, including a wooden deck for the sake of the dancers and the installation of permanent lighting positions, shown here in drawings prepared Herschel Harrington, the expert Atlanta lighting man. Elevation view:

Plan view:

1954 season program cover.

Contrary to Bromo's proposed plan to expand to eight productions, Theatre Under the Stars continued to present a delicious assortment of six a season for the remainder of the decade.

In 1956, the City installed permanent concession locations on both sides of the auditorium, these slim coverings providing the only dry spot in the house in case of deluge. Proper seating was installed in the bleachers.

A production of "Carousel" from 1958 shows the stand microphones used for amplification.

By that time a complex set of rules regarding rain checks had been formulated and included in each program book. The poor actors would race to fill the twenty minutes of "not necessarily continuous performance" at what is known in outdoor drama as Rain Tempo, while the equally-uncovered band and their instruments braved the storms, the personification of "troupers."

Backstage operations are explained in this 1959 feature about "Bells are Ringing" which starred Penny Singleton and featured Margaret Hamilton. IATSE Local #41 members Kermit Spradlin and audio man Lester Cheatham are pictured. Of interest is the use of a turntable for the season and the fact that producer/director used a megaphone to bark his commands to the stage during rehearsals.

Annual operating deficits were covered by business leaders, but there was simply too much rain in 1958 and 1959. The shortfall was underwritten possibly by Bromo Seltzer himself, according to her excellent history, "The Hundred Days: Atlanta Municipal Theatre in The Atlanta Memorial Arts Center," authored by Constitution Drama Editor Diane Thomas in 1969.

Enter Christopher Manos, the son of struggling Greek immigrants who had landed in Cleveland. He began his theatrical career as a dancer in the 1940's, and in 1956 as an aspiring producer in New York City, he met and married professional ballerina Glenn Ryman. She hailed from old Atlanta, and her widowed mother Mrs. Glenn Ryman Sr. resided at 2750 Habersham Road.

In 1960, Glenn, Chris Manos, and their two children departed New York for Atlanta where Chris served briefly as a stockbroker for Robinson-Humphrey. In an interview years later, Manos related that he approached Bromo and tactfully stated, "It's stupid how you're running this, and you should hire me." Following a six month trial where Chris worked for free, Bromo hired Chris as Executive Producer, a newly-created position and the first year-round employee. An early bio of Chris Manos:

Chris acted as an observer during the 1960 season, helping to put asses in seats. Below, a well-attended final performance of that season's closer, "Oklahoma!"

The 1961 pre-season opener was "The Phoenix" presented by Mayor Hartsfield in observance of the centennial of the start of the War. Below, the Mayor, conductor Albert Coleman, and Pittman Corry meet to discuss the show. Corry, who with his wife Karen Conrad had created the Southern Ballet, became the resident choreographer for Theatre Under the Stars.

As opposed to Theatre Under the Stars, "The Phoenix" was a community affair.

Chris Manos was convinced that the only way to save Theatre Under the Stars was a complete conversion to star stock, and Bromo gave him the chance to prove it. As a guinea pig, Chris selected Metropolitan Opera Wagnerian mezzo Blanche Thebom who was well-known to Atlanta's Society audience from the Met's annual spring tour which played the Fox. Bromo found an Angel to underwrite her salary and expenses to play in "The King & I," and the star system was born.

"Thirty-five thousand people saw that show," recalled Chris in a 1972 interview. "It was sold out every night, and they were sitting on the grass all around at the park, hanging from the rafters. It was a beautiful, unforgettable experience."

"The King and I" also marked the final performance danced by Mrs. Chris Manos under her stage name, Glenn Ryman.

A 1964 article describing the system gives the credit to Bromo, who says "it took considerable bravado to make the decision," which added $30,000 to the acting budget.

Chris did not invent the star system, he merely made it pay. Jane Kean is given star billing on this 1958 program cover, and Margaret Hamilton, Gypsy Rose Lee, and Penny Singleton played in 1959, the latter playing the role Merman created in "Happy Hunting."

Ethel Merman, "Miss Broadway in person" opened the 1963 season with a bang, setting off national fireworks at the airport when the Key to the City, just handed her, was rescinded "because it's the only one we have." The rarely-billed orchestra included Karl Bevins, Atlanta's chief City traffic engineer and Carlton Palmer who for the Wit's End wrote "They'll be Tearing Up Peachtree."

While Merman played, Bromo passed away, handing off the torch to Chris in July of '63.

In this feature which ran Christmas Eve, Chris Manos took the opportunity to announce the creation of the Winter Play Season, also star stock, effectively doubling the output of Atlanta Municipal Theatre.

The Winter Play Season was presented at the Community Playhouse, a 1921 addition to the mansion which housed the Atlanta Women's Club, in a lovely and intimate 703-seat Broadway-style house, still standing. Upgrades for stars were primarily in the electrics department including the creation of front light positions, both ceiling and box booms. Right are IATSE hands Snooky Freeman and Bob Spadlin on the rail in this hemp house.

By the end of 1964, the star system created and fueled by Chris Manos "had paid off the $236,000 running deficit sustained for several years before his arrival," according to author Diane Thomas. "To his Board of Directors, he had performed a financial miracle."

Chris the Magician brought not only results, but color, excitement and drama to everything he touched. For instance in the 1965 opener, the balloon containing Michael Rennie, rendered below, was suspended from a hidden crane and rose one hundred feet up and over the house for a Grand Finale. That's difficult to top.

Chris put together a machine, seemingly always in the throes of chaos, to produce from scratch, then sell his many attractions. His offices were located at the Howell House, just up the block from the Fox Theatre.

Included in the staff, shown here in 1968, was long-suffering General Manager Michael Parver (center, bottom) and Business Manager Ted Stevens, who later became the first GM of the Fox Theatre. Everyone, including Chris, smoked cigarettes non-stop.

Louise Youngblood Hudson worked for the outfit from 1956 until her death in 1994 at age fifty-two. She was everything that Chris could ask for as an assistant, and more.

Louise Hudson with director Jim Way (right) and composer Don Tucker in July, 1970.

Chris spent money only when forced to, as illustrated in this 1965 article about Louise and the ticket racks.

But Chris had bigger fish to fry, because he was simultaneously taking possession of the other brand new theatre building in town. Having previously merged with the Atlanta Ballet, Municipal Theatre purchased from the Junior League the Atlanta Children's Theatre, created a repertory acting company, and made permanent the Opera company, under the direction of Blanche Thebom, all to become residents of the new Alliance Theatre.

In 1966, an umbrella fund-raising group that included the High Museum, the Atlanta School of Art, and the Atlanta Symphony broke ground for the Memorial Arts Center (now known as the Woodruff) and demolished three mansions (left) to do it. Chris moved his offices to another nearby manse, shown right.

The new offices at 1222 Peachtree:

Chris gives Blanche Thebom a tour of the austere Memorial Arts Center which besides the Alliance Theatre contained a symphony hall and an art museum. Because the constituent group had neglected to include a theatre company under their umbrella, Chris had to pay to play the Alliance, becoming a second-rate tenant and thus not entitled to parasol fundraising. It would become his tomb.

Despite the newspaper description below, the over-seated Alliance (left) was to the Women's Club what the Civic Center was to Chastain: cold, concrete, and unforgiving. Indeed, no front-on photo was ever published of the Alliance house, but it was a smaller version of its adjacent sister, Symphony Hall, right.

Chris chose to program the Alliance with the opposite of the lighter fare for which he well-known and opened with "King Arthur," the epic to end all other epics.

This mammoth show included his Opera, Ballet, and Theatre divisions and was heralded nationally as cultural milestone, reviewed by no less than three critics from the New York Times. Resident LD Nan Porcher and Production Stage Manager Jim Way are shown during a tech of the spectacle, which opened October 29, 1968.

Following several more poorly-attended esoteric productions (running in rep with full stage Atlanta Children's Theatre morning performances), within a hundred days Municipal Theatre went bust, the Alliance went dark, and Chris was left $600,000 in debt. Journal drama critic Terry Kay's sadly observed that this massive failure left Actor's Equity with only one house in Atlanta, the Talley-Ho Dinner Theatre, for God's sake.

But as author Diane Thomas relates, Chris Manos rebounded almost immediately, leaving behind the defunct Municipal Theatre and creating Theatre of the Stars, Inc., and without missing a beat, he played that summer at the Civic Center. By the end of two years, Chris had repaid every cent that he owed.

Next Chris revived the Winter Play Season at the Woman's Club, which he re-christened the Peachtree Playhouse, shown here in 1974. Winter Play Season continued there until there through 1981, and the theatre was converted into a nightclub in 1989.

In 1988, he moved Theatre of the Stars to the Fox Theatre, where he continued to produce through the 2013 season.

Christopher B. Manos produced seven hundred shows over a span of fifty-three years, surely some sort of record. Still smiling enigmatically, Chris poses at the Fox in 2011 with a newly-converted member of Actor's Equity, whose dreams Christopher the Magician had made come true.

Repeated attempts to obtain an interview with Chris Manos for this article were met with defeat. As I am led to understand, Chris (aged 87) is in good health at the time of this writing. He passed away in 2021.

Photos courtesy Georgia State Archives unless otherwise noted, newspaper article excerpts courtesy the AJC archives. Drawings of the Chastain stage courtesy Anita Hoffman, keeper of the Charles Walker-Herschel Harrington collection. "He Escorts the Stars" photo courtesy Joe McKaughan. Tech rehearsal photo courtesy Michael Harris. "King Arthur" ticket stub courtesy Liz Brock. "Guys and Dolls" program page courtesy Jimmy Othuse. Thanks to Scott Hardin, Janice McDonald, Paul Ford, Howard Pousner, Diane Thomas, Terry Kay, Angela Gullicksen, and Garry Motter. "The triumph of hope over experience"-- Oscar Wilde.

To read Howard Pousner's excellent in-depth profile of Chris and to read Helen Smith's interview with Chris, click here.

For a master index of all photo-essays, click here.

Enter Christopher Manos, the son of struggling Greek immigrants who had landed in Cleveland. He began his theatrical career as a dancer in the 1940's, and in 1956 as an aspiring producer in New York City, he met and married professional ballerina Glenn Ryman. She hailed from old Atlanta, and her widowed mother Mrs. Glenn Ryman Sr. resided at 2750 Habersham Road.

In 1960, Glenn, Chris Manos, and their two children departed New York for Atlanta where Chris served briefly as a stockbroker for Robinson-Humphrey. In an interview years later, Manos related that he approached Bromo and tactfully stated, "It's stupid how you're running this, and you should hire me." Following a six month trial where Chris worked for free, Bromo hired Chris as Executive Producer, a newly-created position and the first year-round employee. An early bio of Chris Manos:

Chris acted as an observer during the 1960 season, helping to put asses in seats. Below, a well-attended final performance of that season's closer, "Oklahoma!"

The 1961 pre-season opener was "The Phoenix" presented by Mayor Hartsfield in observance of the centennial of the start of the War. Below, the Mayor, conductor Albert Coleman, and Pittman Corry meet to discuss the show. Corry, who with his wife Karen Conrad had created the Southern Ballet, became the resident choreographer for Theatre Under the Stars.

As opposed to Theatre Under the Stars, "The Phoenix" was a community affair.

Chris Manos was convinced that the only way to save Theatre Under the Stars was a complete conversion to star stock, and Bromo gave him the chance to prove it. As a guinea pig, Chris selected Metropolitan Opera Wagnerian mezzo Blanche Thebom who was well-known to Atlanta's Society audience from the Met's annual spring tour which played the Fox. Bromo found an Angel to underwrite her salary and expenses to play in "The King & I," and the star system was born.

"The King and I" also marked the final performance danced by Mrs. Chris Manos under her stage name, Glenn Ryman.

A 1964 article describing the system gives the credit to Bromo, who says "it took considerable bravado to make the decision," which added $30,000 to the acting budget.

In the same article, Chris is quoted saying "One main and important arrangement we have put into effect is that when season ticket holders acquire tickets this season, they automatically are entitled to those same seats next season," following the very successful model of the perpetually sold-out Met Opera tour. This ad ran on the same page:

Chris did not invent the star system, he merely made it pay. Jane Kean is given star billing on this 1958 program cover, and Margaret Hamilton, Gypsy Rose Lee, and Penny Singleton played in 1959, the latter playing the role Merman created in "Happy Hunting."

Ethel Merman, "Miss Broadway in person" opened the 1963 season with a bang, setting off national fireworks at the airport when the Key to the City, just handed her, was rescinded "because it's the only one we have." The rarely-billed orchestra included Karl Bevins, Atlanta's chief City traffic engineer and Carlton Palmer who for the Wit's End wrote "They'll be Tearing Up Peachtree."

While Merman played, Bromo passed away, handing off the torch to Chris in July of '63.

The Winter Play Season was presented at the Community Playhouse, a 1921 addition to the mansion which housed the Atlanta Women's Club, in a lovely and intimate 703-seat Broadway-style house, still standing. Upgrades for stars were primarily in the electrics department including the creation of front light positions, both ceiling and box booms. Right are IATSE hands Snooky Freeman and Bob Spadlin on the rail in this hemp house.

By the end of 1964, the star system created and fueled by Chris Manos "had paid off the $236,000 running deficit sustained for several years before his arrival," according to author Diane Thomas. "To his Board of Directors, he had performed a financial miracle."

Chris the Magician brought not only results, but color, excitement and drama to everything he touched. For instance in the 1965 opener, the balloon containing Michael Rennie, rendered below, was suspended from a hidden crane and rose one hundred feet up and over the house for a Grand Finale. That's difficult to top.

Chris put together a machine, seemingly always in the throes of chaos, to produce from scratch, then sell his many attractions. His offices were located at the Howell House, just up the block from the Fox Theatre.

Included in the staff, shown here in 1968, was long-suffering General Manager Michael Parver (center, bottom) and Business Manager Ted Stevens, who later became the first GM of the Fox Theatre. Everyone, including Chris, smoked cigarettes non-stop.

Louise Youngblood Hudson worked for the outfit from 1956 until her death in 1994 at age fifty-two. She was everything that Chris could ask for as an assistant, and more.

Two heroes not photographed are Chastain's Head Usher Taylor Jones and House Manager Steve Cucich.

The Municipal Theatre Press Machine never stopped in its quest for free advertising, and stars meant news, as Press Agent Joe McKaughan reveals in this excerpted 1965 AJC Magazine feature, the article itself an example of good press.

Children presented golden press opportunities, and locals were given small roles every season, the 1963 crop shown hear posing in the scene shop while scenic artists, including Charles Walker, toil in the background.

Scott Hardin, the local boy who won the title role in "Oliver!" created his own press by breaking his arm, but in a timely fashion. Producer/Director Eric Mattson signed the boy's cast for the flashbulbs, although the Local Jobber contract was signed by Chris, now the General Manager, New York parlance for the boss. "Oliver!" was directed by Bob Turoff.

After the principals spent all day being interviewed, they spent all night at the Monday dress rehearsal. Thirteen-year-old "Oliver" had a press schedule sufficient to choke a horse, let alone wrestle a bear cub on live TV, which his mother nixed.

Company manager Jeb Stewart served as a mentor to many including child actor Scott Hardin.

Broadway choruses until the late 1960's were comprised of separate singing and dancing corps, operating on the single-threat principal. Rehearsals were sometimes held at the Variety Club, off of the Fox Theatre arcade, and both "singing and dancing ensembles" are pictured on the Fox fire escape.

In 1964 a resident setting designer was hired, and a proper scenic shop was built on the hill above the amphitheatre to manufacture scenery for an ever-expanding season, which would soon include Grand Opera and Ballet (in the Park) and the Winter and Fine Play Seasons downtown.

The 1967 shop crew included Assistant Set Designer Jimmy Othuse (left) and top row, left to right, Glenn Gray the ultimate gopher; smiling IATSE shop carps Snooky Freeman and Billy White; assistant scenic artist John Anderson; and Jack Henry, the outstanding Technical Director. Front row are Property Mistress Elinor Byington and set dresser Marydith Chase, whose primary task was to sprinkle everything with glitter.

Fun, cartooned, and vivid in color, this was Scenery that looked like Scenery. Readying "The Unsinkable Molly Brown" are Mike Destazio pulling flats from stock, a donor in green, and Ann Cairnes, also a mainstay in the box office. The shop was large enough for three forty by sixty foot drops to be painted at once.

Scenery consisted of flats, drops and wagons, and all of it was built out of wood by the two IATSE shop carpenters using hammers and non-electric yankee screwdrivers. Flattage was attached to the wagons with double-headed nails, for easy removal at the strike. Below Frank Dey, Jr. and Snooky Freeman in 1966. Dey's father was the first carloader on the 1929 Fox crew.

Drawings and paint elevations for the scenery were cranked out in the on-site Design office by designer Richard Gullicksen and assistant Michael Harris, shown below in 1965.

Working from paint elevations (lower right) the remarkable chief scenic artist Jim Gordon painted non-stop and at a rapid tempo. Starting with charcoal chalk on a long stick, Gordon would rough out the scenery to scale, then apply the paint, mixed from powder and pungent horse-glue, always simmering on a hot plate. Wagon backing flats, such as the window unit shown standing, were designed in forced perspective to fill in the illusion of depth that the drops provided. Two long and narrow wagons, with flattage attached to the downstage side, comprised the "show traveler" halves which could close off the full width of the stage opening.

In 1963, Chris introduced slave labor into the system, under the guise of Apprenticeships. The 1967 crew under the whip of Apprentice Director Connie Douglass included (back row) Gerrie Hendricks, David Tucker, Billy Long, Michael Pollack, Jeane Yuzna, James Berry, and Mary Louise Pickett. On their knees are Terry Raaen, Virginia Forbes, Barbara Van House, Bob Foreman, Leslie Wender, Sherri Flemister, and Julia Wilson.

The shows played six performances, Tuesday through Sunday, with a changeover on Sunday night and Monday day, rain or shine. Monday night was reserved for the unholy technical and dress rehearsals, which would begin at dusk and end sometime after sunrise Tuesday morning. Below, a shot of the tech table with assistant designer Michael Harris (seated) and designer Richard Gullicksen explaining. The twin beams of light emanate from the carbon arc Super Troupers in the booth.

Besides heavy front sides, two overhead electrics supplied front and back light. By mid-summer, these battens would begin to sag at the center as the lighting instruments, rented from Four Star, filled with water. Inset is Lighting Designer Nananne Porcher (pronounced POR-SHAY) who had the misfortune to design the opening disaster at the new Met in Lincoln Center. Calling a hang, she differentiated between lekos by yelling "Century" or "Kliegl," which had hard and soft beams respectively. Control was provided by four piano boards located backstage left.

Until 1966, there was no effective way to mask the back wall of the shell, as seen in this shot of "Annie Get your Gun." To complete the illusion, Richard Gullicksen designed an inner proscenium arch, framing full-stage drops on one-way traveler tracks.

No photos of the completed effect have been located, but this shot taken from the vantage of the traveler tracks shows the inner proscenium reveal and the cyc electric pipe. The show is the 1966 season closer, Gordon MacRae taking his bow in "Oklahoma!"

As in the two previous Chastain seasons, Chris closed 1967 with a Grand Opera, and the final legit show to play Chastain was Aida. By that time Theatre under the Stars had nine thousand season ticket holders, averaged 150,000 playgoers per season and had a permanent staff of twenty administrative and production people.

The complete roster of Municipal Theatre productions from 1953 to 1967:

Between the rains and the planned change to daylight savings time in Georgia, in December, 1967 Chris decided to vacate Chastain and move to the still-under-construction Civic Center, as announced by Journal Amusements Editor Terry Kay.

Municipal Theatre had been given the use of Chastain rent-free, but the use of the new and untested Civic Center, shown here prior to its opening in March, 1968, cost them $50,000 a year.

The name of the series was changed to "of the Stars," but not before the 1968 season window card had been printed.

The Municipal Theatre Press Machine never stopped in its quest for free advertising, and stars meant news, as Press Agent Joe McKaughan reveals in this excerpted 1965 AJC Magazine feature, the article itself an example of good press.

Children presented golden press opportunities, and locals were given small roles every season, the 1963 crop shown hear posing in the scene shop while scenic artists, including Charles Walker, toil in the background.

Scott Hardin, the local boy who won the title role in "Oliver!" created his own press by breaking his arm, but in a timely fashion. Producer/Director Eric Mattson signed the boy's cast for the flashbulbs, although the Local Jobber contract was signed by Chris, now the General Manager, New York parlance for the boss. "Oliver!" was directed by Bob Turoff.

After the principals spent all day being interviewed, they spent all night at the Monday dress rehearsal. Thirteen-year-old "Oliver" had a press schedule sufficient to choke a horse, let alone wrestle a bear cub on live TV, which his mother nixed.

Company manager Jeb Stewart served as a mentor to many including child actor Scott Hardin.

Broadway choruses until the late 1960's were comprised of separate singing and dancing corps, operating on the single-threat principal. Rehearsals were sometimes held at the Variety Club, off of the Fox Theatre arcade, and both "singing and dancing ensembles" are pictured on the Fox fire escape.

In 1964 a resident setting designer was hired, and a proper scenic shop was built on the hill above the amphitheatre to manufacture scenery for an ever-expanding season, which would soon include Grand Opera and Ballet (in the Park) and the Winter and Fine Play Seasons downtown.

The 1967 shop crew included Assistant Set Designer Jimmy Othuse (left) and top row, left to right, Glenn Gray the ultimate gopher; smiling IATSE shop carps Snooky Freeman and Billy White; assistant scenic artist John Anderson; and Jack Henry, the outstanding Technical Director. Front row are Property Mistress Elinor Byington and set dresser Marydith Chase, whose primary task was to sprinkle everything with glitter.

Fun, cartooned, and vivid in color, this was Scenery that looked like Scenery. Readying "The Unsinkable Molly Brown" are Mike Destazio pulling flats from stock, a donor in green, and Ann Cairnes, also a mainstay in the box office. The shop was large enough for three forty by sixty foot drops to be painted at once.

Scenery consisted of flats, drops and wagons, and all of it was built out of wood by the two IATSE shop carpenters using hammers and non-electric yankee screwdrivers. Flattage was attached to the wagons with double-headed nails, for easy removal at the strike. Below Frank Dey, Jr. and Snooky Freeman in 1966. Dey's father was the first carloader on the 1929 Fox crew.

Drawings and paint elevations for the scenery were cranked out in the on-site Design office by designer Richard Gullicksen and assistant Michael Harris, shown below in 1965.

Working from paint elevations (lower right) the remarkable chief scenic artist Jim Gordon painted non-stop and at a rapid tempo. Starting with charcoal chalk on a long stick, Gordon would rough out the scenery to scale, then apply the paint, mixed from powder and pungent horse-glue, always simmering on a hot plate. Wagon backing flats, such as the window unit shown standing, were designed in forced perspective to fill in the illusion of depth that the drops provided. Two long and narrow wagons, with flattage attached to the downstage side, comprised the "show traveler" halves which could close off the full width of the stage opening.

In 1963, Chris introduced slave labor into the system, under the guise of Apprenticeships. The 1967 crew under the whip of Apprentice Director Connie Douglass included (back row) Gerrie Hendricks, David Tucker, Billy Long, Michael Pollack, Jeane Yuzna, James Berry, and Mary Louise Pickett. On their knees are Terry Raaen, Virginia Forbes, Barbara Van House, Bob Foreman, Leslie Wender, Sherri Flemister, and Julia Wilson.

Besides heavy front sides, two overhead electrics supplied front and back light. By mid-summer, these battens would begin to sag at the center as the lighting instruments, rented from Four Star, filled with water. Inset is Lighting Designer Nananne Porcher (pronounced POR-SHAY) who had the misfortune to design the opening disaster at the new Met in Lincoln Center. Calling a hang, she differentiated between lekos by yelling "Century" or "Kliegl," which had hard and soft beams respectively. Control was provided by four piano boards located backstage left.

Until 1966, there was no effective way to mask the back wall of the shell, as seen in this shot of "Annie Get your Gun." To complete the illusion, Richard Gullicksen designed an inner proscenium arch, framing full-stage drops on one-way traveler tracks.

No photos of the completed effect have been located, but this shot taken from the vantage of the traveler tracks shows the inner proscenium reveal and the cyc electric pipe. The show is the 1966 season closer, Gordon MacRae taking his bow in "Oklahoma!"

The complete roster of Municipal Theatre productions from 1953 to 1967:

Between the rains and the planned change to daylight savings time in Georgia, in December, 1967 Chris decided to vacate Chastain and move to the still-under-construction Civic Center, as announced by Journal Amusements Editor Terry Kay.

Municipal Theatre had been given the use of Chastain rent-free, but the use of the new and untested Civic Center, shown here prior to its opening in March, 1968, cost them $50,000 a year.

But Chris had bigger fish to fry, because he was simultaneously taking possession of the other brand new theatre building in town. Having previously merged with the Atlanta Ballet, Municipal Theatre purchased from the Junior League the Atlanta Children's Theatre, created a repertory acting company, and made permanent the Opera company, under the direction of Blanche Thebom, all to become residents of the new Alliance Theatre.

In 1966, an umbrella fund-raising group that included the High Museum, the Atlanta School of Art, and the Atlanta Symphony broke ground for the Memorial Arts Center (now known as the Woodruff) and demolished three mansions (left) to do it. Chris moved his offices to another nearby manse, shown right.

The new offices at 1222 Peachtree:

Chris gives Blanche Thebom a tour of the austere Memorial Arts Center which besides the Alliance Theatre contained a symphony hall and an art museum. Because the constituent group had neglected to include a theatre company under their umbrella, Chris had to pay to play the Alliance, becoming a second-rate tenant and thus not entitled to parasol fundraising. It would become his tomb.

Despite the newspaper description below, the over-seated Alliance (left) was to the Women's Club what the Civic Center was to Chastain: cold, concrete, and unforgiving. Indeed, no front-on photo was ever published of the Alliance house, but it was a smaller version of its adjacent sister, Symphony Hall, right.

Chris chose to program the Alliance with the opposite of the lighter fare for which he well-known and opened with "King Arthur," the epic to end all other epics.

Following several more poorly-attended esoteric productions (running in rep with full stage Atlanta Children's Theatre morning performances), within a hundred days Municipal Theatre went bust, the Alliance went dark, and Chris was left $600,000 in debt. Journal drama critic Terry Kay's sadly observed that this massive failure left Actor's Equity with only one house in Atlanta, the Talley-Ho Dinner Theatre, for God's sake.

But as author Diane Thomas relates, Chris Manos rebounded almost immediately, leaving behind the defunct Municipal Theatre and creating Theatre of the Stars, Inc., and without missing a beat, he played that summer at the Civic Center. By the end of two years, Chris had repaid every cent that he owed.

Next Chris revived the Winter Play Season at the Woman's Club, which he re-christened the Peachtree Playhouse, shown here in 1974. Winter Play Season continued there until there through 1981, and the theatre was converted into a nightclub in 1989.

In 1988, he moved Theatre of the Stars to the Fox Theatre, where he continued to produce through the 2013 season.

Christopher B. Manos produced seven hundred shows over a span of fifty-three years, surely some sort of record. Still smiling enigmatically, Chris poses at the Fox in 2011 with a newly-converted member of Actor's Equity, whose dreams Christopher the Magician had made come true.

Repeated attempts to obtain an interview with Chris Manos for this article were met with defeat. As I am led to understand, Chris (aged 87) is in good health at the time of this writing. He passed away in 2021.

Photos courtesy Georgia State Archives unless otherwise noted, newspaper article excerpts courtesy the AJC archives. Drawings of the Chastain stage courtesy Anita Hoffman, keeper of the Charles Walker-Herschel Harrington collection. "He Escorts the Stars" photo courtesy Joe McKaughan. Tech rehearsal photo courtesy Michael Harris. "King Arthur" ticket stub courtesy Liz Brock. "Guys and Dolls" program page courtesy Jimmy Othuse. Thanks to Scott Hardin, Janice McDonald, Paul Ford, Howard Pousner, Diane Thomas, Terry Kay, Angela Gullicksen, and Garry Motter. "The triumph of hope over experience"-- Oscar Wilde.

To read Howard Pousner's excellent in-depth profile of Chris and to read Helen Smith's interview with Chris, click here.

For a master index of all photo-essays, click here.

March, 2018, revised August 2021.