Note: The last performance at the Civic Center was in the fall of 2015 at which time the facility was closed.

The Confederate Georgia flag flies above the Lincoln Center-esque facade.

At night time in 1968.

Shown after a 2001 upgrade with a now-enclosed courtyard, the Theatre continues to suffer from its location. In the 1970's, the wrongly-named Civic Center Marta subway station was built a half mile away, an indirect ugly and unthinkable nighttime walk in an area increasingly populated by homeless from St. Luke's feeding center.

The stage house and below its three-bay loading dock. The modernistic Moorish window details mimic the Fox Theatre.

East elevation, 1968.

The Mezzanine Foyer in 1968 with (gasp!) ashtrays.

The Foyer today, its pricey Rambusch chandeliers scintillate in stark contrast to the otherwise minimally decorated interior. Rambusch is an old NYC firm that specializes in crafting custom lighting fixtures, and their work is represented at the NY Met, the long-gone NY Roxy Theatre, and the Fox.

From the start, those chandeliers were the Theatre's most photogenic feature, as shown on the cover of this April, 1968 AJC Sunday magazine.

The vast acoustical-cloud-covered auditorium, the balcony miles away from the stage, and sweeping "box" section, 1968.

Such was not the case at the old Auditorium, the Symphony shown here in a more intimate arrangement (albeit makeshift), six days previous.

The Municipal Auditorium, shown below in its 1909 "auditorium-armory" incarnation, the year before the Met Opera made its first visit to Atlanta when a proper stage house was hastily constructed to their specifications.

Opera at the Auditorium which had no orchestra pit.

A view of the auditorium and booth:

A symphony rehearsal with the floor cleared of seating risers and wooden seats:

Once the Fox opened as a legit house, the Auditorium was no longer needed, closed in 1979 and was demolished two years later. These two excellent shots were taken by Wayne Daniel.

The remnants of the Peter Clark T-track fly system can be seen here.

Ralph Bridges 1967-68 season illustrates the attractions moved from the Auditorium to the Civic Center.

The Metropolitan Opera moved from the Auditorium to the Fox Theatre beginning in 1947, at a time when the Fox was a first-run movie house and accepted no other live bookings.

The annual spring tour at the 4600-seat Fox was the social event for upper-crust Atlanta, perpetually sold out in great blocks to subscribers, many of whom attended all seven operas in a row.

Met impresario Rudolf Bing at the Fox arcade doors with Atlanta matron Mrs. Harold Cooledge when things were Grande.

Charles Walker (of the World):

A video clip from that production, http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=AdGPF5-kSVA

Plan at stage basement

Plan at stage

Stage plan showing flies

Flies detail, showing the original eight traveler curtains.

Auditorium reflected ceiling plan

Auditorium section

From midstage right:

In the flies can be seen the from left to right, the house valance, the plaster inner proscenium arch, the Valance borderlight, and the asbestos curtain (its bottom painted black).

Asbestos is our friend.

The Switchboard jump as seen from the upper operating rail. Only the right hand portion of the switchboard is visible in this photograph.

"Scene One" controllers.

House light section (center) and "scene two" on the right. The imposing twin Variac knobs control merely the intensity of the pilot lights within the backlit faders.

Houselight faders.

Houselight masters. These levers are a sort of split crossfader, but spaced too far apart to work as such.

Stage masters were similarly designed, positioned on the desk of the switchboard.

"Scene Two."

Faders up close.

The faders were manufactured by Ward Leonard of Mt. Vernon, NY. Leonard manufactured its own boards dating back to the early 1900s, and they built and supplied resistance dimmers for Hub, Westinghouse and other companies that chose not to manufacture their own dimmers. The Hub board at Atlanta's 1929 Fox Theatre incorporates two hundred Ward Leonard resistance plates.

The fifty 10K stage dimmers are located in the substage in room-size rack, the left section shown here.

The empty right section of the rack was intended to contain the other forty future dimmers and ten non-dims.

Center section of the rack contains the guts, buses, and main disconnect.

The SCR dimmers are also Ward Leonard. Dig the 90A breakers.

A separate dimmer rack for houselights is located in an upstairs room at the elevation of the first auditorium bridge.

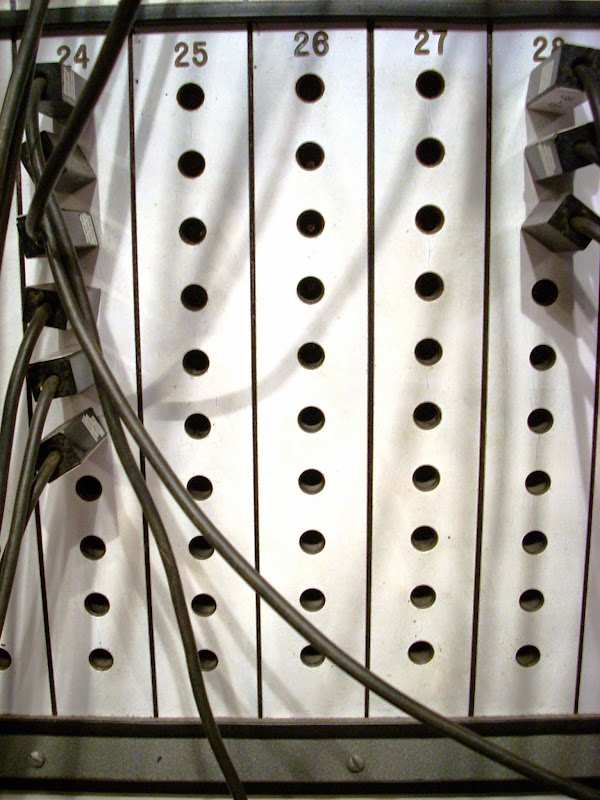

To connect the 451 stage branch circuits to the fifty 10K stage dimmers is a Lighting Equipment Company patch panel, designed for "hard" as opposed to electronic "soft" patching, located substage left, across from the counterweight arbor well. This is a view looking downstage.

The patch bay jacks for the 50 dimmers are located center. Branch breakers to each side of the jack field are tied to each of the overhead plugs which represent the 451 20A stage circuits. In this photo some of the plugs are connected directly into an ETC rack (left) instead of the the house board.

Right bank of branch breakers.

Typical bank of overhead plugs, showing six of the nine footlight circuits.

A typical plug, this one for the FC (foots-center) G (green) circuit.

The circuit breakers for these footlight branch circuits. The breaker layout and labeling is identical to that used in Hub Electric of Elm Grove, Illinois, so it is very likely that this panel was built by Hub for Lighting Equipment Corporation.

Inside the patch are the ten pound pulley-weights which allow the plug cords to retract upwards when not in use.

The "magic sheet" for all branch circuits: three auditorium "bridges," ten electric pipes (including Valance borderlight), torms, foots and floor pockets

Typical jack field.

The all-important panel lights dimmer. This is the classic Superior Electric WBD (wall box dimmer) the first SCR sold for home and office installation beginning in the mid-1950s. They require an oversize mounting box.

The intercom jacks to connect patch operator to the switchboard. With only fifty dimmers, re-patches during performances were routine but tricky because they had to be accomplished only once the affected dimmer was released.

"Wattmeters" which were ammeters provided a fast way to determine if a load was plugged, if a lamp was good, or what the draw of a given branch circuit was, because the total 10K load was additive and could not be exceeded.

The Patch Panel name plate.

Looking upstage, the Circular stair at the end of the patch room took one back up to the deck.

One of the nine Major Corporation three-color disappearing footlight sections, view from stage left.

A terrible "no-no," a receptacle located with the smoke pocket!

One of twenty-two stage deck floor pockets, manufactured by the Major Corporation.

Four (very dirty) porcelain females to receive the rare triangular grounded "stage plugs," which were invented in the 50's to satisfy NYC TV studio installs and were known as "TV plugs," pejoratively of course. Ungrounded stage plugs date back to the 1890's.

Torms (tormentor) positions left and right, as with the nine stage electric pipes utilize Major aluminum connector strips (shown here to the left) with 12" pigtails terminating in grounded pin connectors. In 1968 no lighting instruments were grounded, thus the grounded pin connector was designed to be compatible.

The Atlanta Civic Center stage rigging was manufactured and installed by SECOA of Minnesota, which unlike Lighting Equipment Company, Ward-Leonard, Hub Electric or the Major Corporation, is still in business today. There are two operating rails, this one at deck level and the other 18 feet above.

A view of the substage arbor well from the stage level.

And the same with a different exposure.

A view of the upper operating rail looking downstage.

At the furthest downstage end of the upper operating rail is the mule winch, shown here.

The wire rope reels from the drum and heads downwards to a substage mule block

which redirects it upstage along an I-beam track...

...to a block which can lock down to the track at any lineset, where the cable is the redirected upwards...

...to a snatch hook, shown here in repose, which can be clipped into the specially-placed offstage eye on any given arbor. Quite an excellent and sexy system which eliminates the horror of ripping an arbor out of its T-track.

Access to the auditorium lighting bridges is at the top of the southwest exit stair located offstage left. A self-propelled stagehand-cage suspended from ceiling tracks can traverse the upper proscenium arch to provide access to the dead-hung house valance.

A view from above the acoustical clouds,

There are five "auditorium lighting bridges," but due to a tragic design error, probably traceable to acousticians Bolt Beranek and Newman, the view from all but one bridge is obscured by the acoustical clouds. I like to imagine the screaming that went on once this error had been fully comprehended. There was no money remaining in the construction till to make a fix.

Commencing with that nearest the stage, Auditorium Bridge One, with eighteen circuits which remain virginal.

From Bridge One, the massive central cluster, with Altec Manta-Ray horns below the bass cabinet, the system unused for many years.

Bridge Two, with 36 circuits and the only unobstructed view to the stage.

Another view of Bridge Two. IA hand Phil Hutcheson tells that he and Lee Betts hung the pipe batten shown here in 1973 as a "temporary" solution for the lack of a proper pipe.

Bridge Three, no circuits but plenty of clouds.

Bridge Four, 30 unused circuits.

Including Circuit Number One.

Connector strip detail.

Circuitless Bridge Five.

Five affords a fine stage view for the tourist.

What with (the idea of) such excellent beam or cove positions, there was no need to provide a balcony rail position...

...or box booms which according to house electrician Darryl Hilton were envisioned to be located above the exit doors, two per side.

So long, dear Theatre.

Extended interview with Harold Montague, AJC Sunday Magazine, April 21, 1968

In this piece, Mr. Montague disparages the Fox Theatre saying that "it works for opera because the Met are used to it" and that "the Fox was designed in the days of Burlesque." The fact is that the Fox was built as a super-deluxe Movie Palace (4000+ seats) and was originally a Presentation House, playing talkies and stage shows on the same bill, four-a-day. The Fox had no relationship with Burlesque whatsoever. Also, Montague references Harry Niebruegge, longtime manager of the Municipal Auditorium.

The Metropolitan's Rudolf Bing tour the Civic Center, May 8, 1968, Journal (Note: Future Met manager Joe Volpe is misspelled "Bolpe.")

Hair opens with a bang, November 24, 1971, Journal

Come November, 2014, Atlanta will be without a municipal auditorium for the first time in 105 years. Those elected to run Atlanta have decided to write off the city-owned-and-operated Atlanta Civic Center, which under their management lost almost half a million dollars in 2013 and has been booked for a paltry thirty days since January. Following a final one-night rental, it will shutter for good on October 19th.

October 17, 2014 AJC

###

The Atlanta Civic Center opened on March 7, 1968, which makes it forty-six years old this year (2014), coincidentally the same age as the Fox Theatre when it was saved from the wrecking ball in 1975. The theatre portion cost $4.5 million, the entire project $9 million. As the years have gone by, the building has lost its tenants, either to other facilities or because the presenters ceased to exist. It was the home to the Metropolitan Opera spring tour for 19 seasons, Theater of the Stars for 21, the Nutcracker for six, and more recently the Atlanta Opera for five. Other primary presenters were the Atlanta Music Club and Ralph Bridges' Famous Artist series.

Its major selling point is an excellent stage, the largest in the Southeast, fifty wide and fifty deep, with decent wings, a fine loading dock, and an 85 foot high grid loft.

The problem is that no one particularly cares for its 4600-seat auditorium, described in a 2007 Atlanta Magazine spread as "as large as a convention hall and as charmless as a high school auditorium," and cited for its "mausoleum ambiance and cavern-like acoustics" by the AJC. Perhaps a canny developer can retain the stage and construct a better auditorium.

This article will review the early history of the Robert F. Maddox Hall of the Civic Center and will provide a detailed tour of its backstage equipment.

###

The Atlanta Civic Center which includes a separate exhibition hall (not shown below) was termed a "Civic Camelot," by Atlanta Magazine, the Theatre shown here in a 1965 rendering.

Constructed in the spirit of Lyndon Johnson's "Great Society" wherein all urban ills could be solved by a magic bulldozer, the Civic Center never overcame the stigma of having been built on the site of Buttermilk Bottom, a crime-infested valley of ramshackle dwellings, their removal financed by federal Urban Renewal dollars. Below right is Mayor Hartsfield touring the aromatic Bottom in 1956, from a Life Magazine article.

The Atlanta Civic Center under construction in May 1966, Georgia Baptist Hospital in the distance.

The completed Theatre in March, 1968, showing the large stage house and the two-story dressing rooms wings which surround it.

The Confederate Georgia flag flies above the Lincoln Center-esque facade.

At night time in 1968.

Shown after a 2001 upgrade with a now-enclosed courtyard, the Theatre continues to suffer from its location. In the 1970's, the wrongly-named Civic Center Marta subway station was built a half mile away, an indirect ugly and unthinkable nighttime walk in an area increasingly populated by homeless from St. Luke's feeding center.

The stage house and below its three-bay loading dock. The modernistic Moorish window details mimic the Fox Theatre.

East elevation, 1968.

The Mezzanine Foyer in 1968 with (gasp!) ashtrays.

The Foyer today, its pricey Rambusch chandeliers scintillate in stark contrast to the otherwise minimally decorated interior. Rambusch is an old NYC firm that specializes in crafting custom lighting fixtures, and their work is represented at the NY Met, the long-gone NY Roxy Theatre, and the Fox.

From the start, those chandeliers were the Theatre's most photogenic feature, as shown on the cover of this April, 1968 AJC Sunday magazine.

The vast acoustical-cloud-covered auditorium, the balcony miles away from the stage, and sweeping "box" section, 1968.

###

The Civic Center along with the Atlanta Stadium were the major brick-and mortar accomplishments of Mayor Ivan Allen, Jr. who served from 1962 until 1970, the last Mayor to have a wife in the Junior League.

The architect was Harold Montague, from a local firm.

(Evidence indicates the the Civic Center was Montague's first and only theatre design. To read more about him, scroll to the end of this article.)

The Theatre was envisioned as a combination opera house and symphony hall, originally equipped with an acoustical shell and rows of borderlights above the stage for the latter purpose.

For some reason lost to time, the project hired as acoustical consultants the Boston firm of Bolt Beranek & Newman, in 1968 best known for its work on New York's Philharmonic Hall, which had opened in 1962 to dreadful reviews. The first building in Lincoln Center was the well-publicized worst acoustical disaster of all time.

If the Civic Center had its own acoustical problems, they were not immediately identified in the press coverage of the March, 1968 opening performance by the Atlanta Symphony.

The Constitution gushed, "Symphony Rocks New Civic Center" and "Acoustics at New Center Project Symphony at Best."

"First impressions are always subject to correction," wisely wrote music critic Jerry Etheridge, "but from where this reviewer sat Thursday night, acoustics in the hall were simply superb."

A view of the stage on opening night shows the original gold house drapes, and downstage right can be seen a television camera. WSB-TV broadcast the concert live and in color in a two hour special. Perhaps the acoustical gurus ordained that the vast pit remain vacant so that the band would sit entirely under the sound shell.

Such was not the case at the old Auditorium, the Symphony shown here in a more intimate arrangement (albeit makeshift), six days previous.

Despite the raves, the Symphony would be an extremely short-lived tenant of the house because their own venue in the Memorial Arts Center would open that autumn, the 1800-seat Symphony Hall where they currently reside.

Then there was the Opera problem.

(To read more about the Opera and the Fox, click here.)

In Mayor Ivan Allen's mind, the primary function of the new Civic Center would be to provide a theatre more racially acceptable than the Fox for the spring tour of the Metropolitan Opera. It would also provide an alternative to the decrepit Municipal Auditorium, located deep downtown on Courtland at Edgewood.

The Municipal Auditorium, shown below in its 1909 "auditorium-armory" incarnation, the year before the Met Opera made its first visit to Atlanta when a proper stage house was hastily constructed to their specifications.

To the right, the original room gutted for the 1936 WPA renovation. The man facing upstage is standing on the circular stage platform also shown in the previous photo. The I-beam directly above his head is the 1910 proscenium arch constructed for the opera.

The predictable result of the renovation was an unattractive 5200-seat barn. Among its many shortcomings was the fact that the orchestra seating was temporary, routinely removed to make an arena for boxing, wrestling, and the annual Holiday on Ice. Smaller roadshows played the midtown 1900-seat Tower nee Erlanger until it was gutted in 1962 and the 700-seat Women's Club Community Playhouse (Peachtree Playhouse) which survives as a nightclub. Below, the Atlanta Symphony at the improved Auditorium.

Opera at the Auditorium which had no orchestra pit.

A view of the auditorium and booth:

A symphony rehearsal with the floor cleared of seating risers and wooden seats:

Once the Fox opened as a legit house, the Auditorium was no longer needed, closed in 1979 and was demolished two years later. These two excellent shots were taken by Wayne Daniel.

The remnants of the Peter Clark T-track fly system can be seen here.

Ralph Bridges 1967-68 season illustrates the attractions moved from the Auditorium to the Civic Center.

The Metropolitan Opera moved from the Auditorium to the Fox Theatre beginning in 1947, at a time when the Fox was a first-run movie house and accepted no other live bookings.

The annual spring tour at the 4600-seat Fox was the social event for upper-crust Atlanta, perpetually sold out in great blocks to subscribers, many of whom attended all seven operas in a row.

Met impresario Rudolf Bing at the Fox arcade doors with Atlanta matron Mrs. Harold Cooledge when things were Grande.

In 1963, as part of a modernization program intended to curb declining movie attendance, the Fox installed large rocking-chair seats in the orchestra section, reducing the seating capacity from 4600 to 3993 two seasons after Bing, bowing to pressure from a civil rights group, insisted that the Fox be desegregated for Opera performances.

Thus there were virtually no "free" tickets available for social experimentation. Ivan Allen wanted a new venue with the original complement of seats.

But when push came to shove, both Rudolf Bing and the Atlanta Music Festival (the local presenter) dragged their feet. Despite the fact that the Civic Center was completed prior to the 1968 Met season, the Opera snubbed them, and played the Fox.

Following Opera week, this Constitution editorial appeared:

The Opera moved to the Civic Center the next season and like it or not, played there until 1986 when the company ceased to tour. But it was never the same, because matrons thought that metaphorically dragging their furs through Buttermilk Bottom was a far cry from parading across Klieg-lit Peachtree Street in their minks and finery, under the stately shadows of the Ponce de leon Apartments and the Georgian Terrace where the singers stayed. But such was the price of civic progress.

###

The Civic Center's errant acoustical properties first reared their ugly head with a different tenant, one that used amplification.

Municipal Theatre had presented Theater Under the Stars, a six-week series of musicals at the 6000-seat Chastain Park amphitheater since 1953, and under the direction of Christopher Manos in 1963 they began presenting stars. For Manos, the Civic Center was a blessing because the introduction of daylight savings time in 1968 brought an end to musical comedy out of doors, and the possibility of matinees and the lack of rain more than compensated for the loss of 1400 seats.

Commencing Tuesday, July 9, 1968, Chris Manos began his twenty-one year residency at the Civic Center, with Juliet Prowse starring in Irma La Douce.

Constitution dramatic critic Diane Thomas called the show "Magnifique," continuing, "Irma bids fair to be the best production Theater Under the Stars, now Theater of the Stars, has ever done."

But Miss Thomas' similar rave for Barbara Cook's The Sound of Music warned of "a sound system that is far from worthy of the production." Despite annual adjustments and several costly new installations, the auditorium of the Civic Center defied corrective amplification of the spoken voice. Manos moved the series to the Fox Theatre in 1989, which had been restored to its original 4600 seats, where it played until the company's demise last year.

###

From the beginning, manager Roy O. Elrod refused to allow presentations which did not conform to the Civc Center's "image" as a presenter of family-style entertainment.

In 1971, the Federal Court system ruled that the Civic Center could not prohibit Ralph Bridges from presenting the stage play Hair there. Manager Roy Elrod claimed that to present such material would result in great financial harm to the house.

To read more about the lawsuit, go to

http://leagle.com/decision/1971968334FSupp634_1857.xml/SOUTHEASTERN%20PROMOTIONS,%20LTD.%20v.%20CITY%20OF%20ATLANTA,%20GA. To read about the bomb that went off in the balcony when Hair played, scroll to the end of the article.

###

A relic in a substage storeroom is an ancient lighting unit from Herschel Harrington's 10th Street lighting rental studio, operated for many years by Charles Walker.

The unit:

Charles Walker (of the World):

Charles was the professional tech man and lighting designer for the First Baptist Church' annual Passion Play which had the longest run of any other attraction at the Civic Center: thirty-five seasons, until 2011 when it ceased production, four years after his death.

"The Ascension," from the 2009 production.

From the 2011 production, showing the pit elevator down.

A video clip from that production, http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=AdGPF5-kSVA

###

The back stage at the Civic Center is remarkably unchanged from 1968, having been kept in good shape by the City and lovingly tended to by IATSE Local 927 House Electrician Darryl Hilton, House Property Man Hank Collins, and House Audio Man Cotis Weaver. Hilton and Weaver have been Civic Center stage department heads for 23 years. Stagehand Lee Freeman holds the distinction of having worked both the first and final productions, with a thousand wedged in between.

Atlanta Civic Center stage plans and drawings:

Plan at stage basement

Plan at stage

Stage plan showing flies

Flies detail, showing the original eight traveler curtains.

Auditorium reflected ceiling plan

Auditorium section

A view of the stage during a recent load-in, portions of the front orchestra seating temporarily removed. Pit lift is at stage level forming a thrust.

From midstage right:

In the flies can be seen the from left to right, the house valance, the plaster inner proscenium arch, the Valance borderlight, and the asbestos curtain (its bottom painted black).

View from down left, upper operating rail. Borderlight cables for the downstage electrics and the underside of the grid loft, the main curtain (fully flown) at the bottom of the shot.

From upstage left, the stage deck level operating rail, the stage manager's position and above it, the switchboard "jump." At the edge of the arch is the torm lighting position.

Asbestos is our friend.

The nerve center of the theatre is the lighting switchboard, with a manufacturer's label saying "Lighting Equipment Company of Elk Grove Village, Illinois." However, the control section is definitely a Ward-Leonard Solitrol.

The Civic Center board incorporated a two-scene preset (with faders for A & B subgroups) controlling 90 channels, plus houselights. Only fifty dimmers were ever installed, each one with a 10,000 watt capacity.

The Switchboard jump as seen from the upper operating rail. Only the right hand portion of the switchboard is visible in this photograph.

"Scene One" controllers.

House light section (center) and "scene two" on the right. The imposing twin Variac knobs control merely the intensity of the pilot lights within the backlit faders.

Houselight faders.

Houselight masters. These levers are a sort of split crossfader, but spaced too far apart to work as such.

Stage masters were similarly designed, positioned on the desk of the switchboard.

Faders up close.

The faders were manufactured by Ward Leonard of Mt. Vernon, NY. Leonard manufactured its own boards dating back to the early 1900s, and they built and supplied resistance dimmers for Hub, Westinghouse and other companies that chose not to manufacture their own dimmers. The Hub board at Atlanta's 1929 Fox Theatre incorporates two hundred Ward Leonard resistance plates.

Also on the switchboard jump are the controls for the orchestra pit lift and the mule winch. The pit lift was one of three Dover Elevator pit installs in 1968, the other two at the Memorial Arts Center. A duplicate control is located in a pit deck trap.

The fifty 10K stage dimmers are located in the substage in room-size rack, the left section shown here.

The empty right section of the rack was intended to contain the other forty future dimmers and ten non-dims.

Center section of the rack contains the guts, buses, and main disconnect.

The SCR dimmers are also Ward Leonard. Dig the 90A breakers.

A separate dimmer rack for houselights is located in an upstairs room at the elevation of the first auditorium bridge.

To connect the 451 stage branch circuits to the fifty 10K stage dimmers is a Lighting Equipment Company patch panel, designed for "hard" as opposed to electronic "soft" patching, located substage left, across from the counterweight arbor well. This is a view looking downstage.

The patch bay jacks for the 50 dimmers are located center. Branch breakers to each side of the jack field are tied to each of the overhead plugs which represent the 451 20A stage circuits. In this photo some of the plugs are connected directly into an ETC rack (left) instead of the the house board.

Right bank of branch breakers.

Typical bank of overhead plugs, showing six of the nine footlight circuits.

A typical plug, this one for the FC (foots-center) G (green) circuit.

The circuit breakers for these footlight branch circuits. The breaker layout and labeling is identical to that used in Hub Electric of Elm Grove, Illinois, so it is very likely that this panel was built by Hub for Lighting Equipment Corporation.

Inside the patch are the ten pound pulley-weights which allow the plug cords to retract upwards when not in use.

The "magic sheet" for all branch circuits: three auditorium "bridges," ten electric pipes (including Valance borderlight), torms, foots and floor pockets

Typical jack field.

The all-important panel lights dimmer. This is the classic Superior Electric WBD (wall box dimmer) the first SCR sold for home and office installation beginning in the mid-1950s. They require an oversize mounting box.

The intercom jacks to connect patch operator to the switchboard. With only fifty dimmers, re-patches during performances were routine but tricky because they had to be accomplished only once the affected dimmer was released.

"Wattmeters" which were ammeters provided a fast way to determine if a load was plugged, if a lamp was good, or what the draw of a given branch circuit was, because the total 10K load was additive and could not be exceeded.

The Patch Panel name plate.

Looking upstage, the Circular stair at the end of the patch room took one back up to the deck.

One of the nine Major Corporation three-color disappearing footlight sections, view from stage left.

A terrible "no-no," a receptacle located with the smoke pocket!

One of twenty-two stage deck floor pockets, manufactured by the Major Corporation.

Four (very dirty) porcelain females to receive the rare triangular grounded "stage plugs," which were invented in the 50's to satisfy NYC TV studio installs and were known as "TV plugs," pejoratively of course. Ungrounded stage plugs date back to the 1890's.

Torms (tormentor) positions left and right, as with the nine stage electric pipes utilize Major aluminum connector strips (shown here to the left) with 12" pigtails terminating in grounded pin connectors. In 1968 no lighting instruments were grounded, thus the grounded pin connector was designed to be compatible.

The Atlanta Civic Center stage rigging was manufactured and installed by SECOA of Minnesota, which unlike Lighting Equipment Company, Ward-Leonard, Hub Electric or the Major Corporation, is still in business today. There are two operating rails, this one at deck level and the other 18 feet above.

A view of the substage arbor well from the stage level.

And the same with a different exposure.

A view of the upper operating rail looking downstage.

At the furthest downstage end of the upper operating rail is the mule winch, shown here.

The wire rope reels from the drum and heads downwards to a substage mule block

which redirects it upstage along an I-beam track...

...to a block which can lock down to the track at any lineset, where the cable is the redirected upwards...

...to a snatch hook, shown here in repose, which can be clipped into the specially-placed offstage eye on any given arbor. Quite an excellent and sexy system which eliminates the horror of ripping an arbor out of its T-track.

Access to the auditorium lighting bridges is at the top of the southwest exit stair located offstage left. A self-propelled stagehand-cage suspended from ceiling tracks can traverse the upper proscenium arch to provide access to the dead-hung house valance.

A view from above the acoustical clouds,

There are five "auditorium lighting bridges," but due to a tragic design error, probably traceable to acousticians Bolt Beranek and Newman, the view from all but one bridge is obscured by the acoustical clouds. I like to imagine the screaming that went on once this error had been fully comprehended. There was no money remaining in the construction till to make a fix.

Commencing with that nearest the stage, Auditorium Bridge One, with eighteen circuits which remain virginal.

From Bridge One, the massive central cluster, with Altec Manta-Ray horns below the bass cabinet, the system unused for many years.

Bridge Two, with 36 circuits and the only unobstructed view to the stage.

Another view of Bridge Two. IA hand Phil Hutcheson tells that he and Lee Betts hung the pipe batten shown here in 1973 as a "temporary" solution for the lack of a proper pipe.

Bridge Three, no circuits but plenty of clouds.

Bridge Four, 30 unused circuits.

Including Circuit Number One.

Connector strip detail.

Circuitless Bridge Five.

Five affords a fine stage view for the tourist.

...or box booms which according to house electrician Darryl Hilton were envisioned to be located above the exit doors, two per side.

So long, dear Theatre.

--Bob Foreman (c) 2014

Further reading:

Open House announcement, March 3, 1968, Constitution

Review of opening night, March 8, 1968 Constitution

Review of opening night, March 8, 1968 Constitution

Interview with architect Harold Montague, Constitution, March 9, 1968

Extended interview with Harold Montague, AJC Sunday Magazine, April 21, 1968

In this piece, Mr. Montague disparages the Fox Theatre saying that "it works for opera because the Met are used to it" and that "the Fox was designed in the days of Burlesque." The fact is that the Fox was built as a super-deluxe Movie Palace (4000+ seats) and was originally a Presentation House, playing talkies and stage shows on the same bill, four-a-day. The Fox had no relationship with Burlesque whatsoever. Also, Montague references Harry Niebruegge, longtime manager of the Municipal Auditorium.

The Metropolitan's Rudolf Bing tour the Civic Center, May 8, 1968, Journal (Note: Future Met manager Joe Volpe is misspelled "Bolpe.")

Hair opens with a bang, November 24, 1971, Journal

For a master index of all photo-essays, click here.

.JPG)