According to the Director of Restoration, "Joe Booth was the best architect I ever worked with for many reasons, but primarily because he understood it was a restoration and not a new design. This would seem obvious, but we had at OSPAC (Ocean State, now Providence Performing Arts Center) a man who didn't get it. Joe Booth was also a superb draftsman, extremely personable, and he never made mistakes." Joe Booth was affiliated with Dyer/Brown & Associates of Boston and New Bedford. WHALE stands for Waterfront Historic Area LeaguE.

According to the Director of Restoration, "Joe Booth was the best architect I ever worked with for many reasons, but primarily because he understood it was a restoration and not a new design. This would seem obvious, but we had at OSPAC (Ocean State, now Providence Performing Arts Center) a man who didn't get it. Joe Booth was also a superb draftsman, extremely personable, and he never made mistakes." Joe Booth was affiliated with Dyer/Brown & Associates of Boston and New Bedford. WHALE stands for Waterfront Historic Area LeaguE.The restoration of New Bedford's Zeiterion Theatre was divided into two phases:

Phase I June- September, 1982-- $200,000, four months.

Theatre opened with Shirley Jones.

Phase II April- July, 1983-- $1.2 million, three-and-a-half months.

Theatre re-opened with Tommy Dorsey.

The Zietz family probably got the theatre's name from Times Square's Criterion Theatre, located on the northeast corner of Broadway and West 44th Street.

Fortunately, the original drawings were still in existence in 1981 when Joe Booth began planning for Phase I. The title block reads: "Leary and Walker, Engineers. May, 1922." And what a magnificent vertical sign the Zeiterion boasted!

Behind the sign, a cornucopia of entertainment flowed from a gargoyle's mouth.John Bullard and Sarah Delano took the newly-hired Director of Restoration on a tour of the theatre. As abandoned movie palaces go, the State was in very good condition, although it wasn't pretty. The 35MM booth equipment was still fully functional.

The front seating had been removed and discarded, but the remaining seats were in good condition. Not visible in the pictures was a huge, beautiful central chandelier. The water damage was minimal. Obtrusive surround loudspeakers for CinemaScope dotted the side walls.

The auditorium was painted for Halloween in yellow and black, but many lovely features were still intact, including the standing rail at the back of the house.

The act announcers on either side of the stage bore mute testimony to the last film shown before closing starring Harry Hamlin and Bubo the Owl. A few weeks after, inside the act announcers was discovered the original paint scheme-- grey and rose.

The stage was empty except for the curved angle-iron CinemaScope picture sheet frame and upstage was a small usher's lounge built out of the old outer lobby doors. The stage rigging was hemp and mostly gone, but the gridloft was rust-free and solid. Everywhere one looked, there were signs of hope.

The stage switchboard controlled stage lights (center) and houselights (right) in three colors, although only the central chandelier and wall brackets still functioned. On the left, the double row of switches beneath the telephone operated the act announcers on either side of the stage. Above and behind the switchboard was the empty organ loft.

The only dressing rooms were on two levels stage left, but they were sprinklered, heated, had counters, and were deemed adequate for Phase I. Following the model of successful startup restorations at the Atlanta Fox and the Providence Loew's, the Director of Restoration divided the job into volunteer projects; staff projects; direct equipment purchases; and a construction contract.

At the conclusion of his initial tour, the Director of Restoration suggested that the theatre be re-named "Zeiterion" because there were so many "Z's" in evidence. Z's, left to right, on the exit valances, the front of the building, above the proscenium arch, and (not shown) on the act announcers. Fortunately, Sarah Delano and John Bullard concurred.

The substage was dirty and litter-filled, but mostly dry. In this corner below the switchboard the new dimmers would be placed. Pencil sketches were made on the drawings using the floor as a writing surface. The grease spot marks the former (and future) location of the organ blower.

The substage, facing downstage right.

The only dressing rooms were on two levels stage left, but they were sprinklered, heated, had counters, and were deemed adequate for Phase I. Following the model of successful startup restorations at the Atlanta Fox and the Providence Loew's, the Director of Restoration divided the job into volunteer projects; staff projects; direct equipment purchases; and a construction contract.

Soon thereafter, architect Joe Booth and his engineers arrived on the scene to draw plans for the contract work, a good low bid resulted, and in early June, 1982 the work began. The first major volunteer job was the demolition of the lobby paneling. Good fortune smiled upon the restoration when it was discovered that the original lobby walls of marble and plaster had not been destroyed, but merely concealed and protected. The inner lobby doors were in perfect shape.

The first non-volunteer task undertaken was to dismantle and remove the curved angle-iron frame and picture sheet from the stage. This job was accomplished by the Director of Restoration with the able assistance of Jim Martins (inset), one of WHALE's maintenance team, recruited by John Bullard from the best upperclassmen of New Bedford's Vocational High. For talented, industrious underprivileged boys like Jim, John Bullard provided an alternative to working in a "fish house."

After the substage had been cleared out by the volunteers, a contract painter finished the room, which would be transformed into the dressing rooms for a star and two spacious chorus rooms in Phase II.

Among the junk removed from the substage were several cans containing reels of silent 35MM film, which had bonded to itself and emitted a sickly sweet odor. Restoration expert Paul Kruger of Providence recommended the immediate removal of the film, warning that it could spontaneously combust.On the stage right side of the substage, a contract electrician works against the clock to complete the all-new stage wiring.Phase I included 24 TTI stage dimmers, a patch, and six house light dimmers. The dimmer packs were purchased out-of-contract to save money.A view of stage right showing the newly re-hemped pinrail and new sand bags. All of the hemp rope was cut down to length and re-used in the Phase II counterweight installation.Downstage of the rail is the new picture sheet and frame.A page from the 1982 tech spec shows the schedule of hemp linesets. New stage drapes included in Phase I were the wine-colored house curtain with teaser and tormentors, three sets of black legs and borders and an upstage black drop. Like the stage dimmers, the drapes, hemp, and picture sheet were purchased out-of-contract.

Finishing touches are being applied to the picture sheet masking. Michael Guy rigged the main drape so that it could travel and open simultaneously, meaning that the pull rope could always remain anchored to the deck.

The results of the Phase I restoration can be seen here. The budget allowed for three sections of the auditorium to be restored: the proscenium arch and side walls; the mural above the arch; and the chandelier and dome cove.

Replacement damask panels were rescued by volunteers from the nearby abandoned Capitol theatre and installed by Healy-Helgesen of Providence, under the expert direction of Lou Fitzpatrick. New wine velour drapes were purchased to match the existing original exit valances.

In this view, the wall and ceilings left unpainted in Phase I can be seen.The ceiling and dome coves were relamped in the original color scheme, red-yellow-blue and the chandelier cleaned and rewired. Barely discernible are the 48 stage lights, intentionally concealed so as not to mar the beauty of the auditorium. The original footlights were reactivated for Phase I curtain warmers.

The replacement seating for the front orchestra was donated by John Rao, owner of the Strand Theatre in Providence, and removed and reinstalled in New Bedford by hard-working Z volunteers-- including WHALE agent John Bullard. Architect Joe Booth took a week off work and with his wife Jean chalked out the new seating plan on the concrete floor, newly-cleaned and painted by non-architect volunteers.

In this view, the illuminated "muses" or dancing girls in the ceiling cove can be seen.

All of the ornamental painting was accomplished by artisan Dennis Tillberg of Providence and the base painting by contract. Below, the restored mural, muses, and proscenium Z.

Dennis Tillberg with his iguana.

In this view, the illuminated "muses" or dancing girls in the ceiling cove can be seen.

All of the ornamental painting was accomplished by artisan Dennis Tillberg of Providence and the base painting by contract. Below, the restored mural, muses, and proscenium Z.

Dennis Tillberg with his iguana.

Volunteer Dick Peterson worked for weeks on the chandelier restoration. The "electrolier" was large enough to sit in and was lowered to working height for the duration.

Five months of hard work are reflected in the newly-painted lobby, completed except for clean-up. Architect Joe Booth had volunteered his time to clean the dark, dingy marble by applying a poultice he had only read about. The next morning the marble was beautiful-- it was like a miracle. Future preservationist Tony Souza had worked as a day laborer on the 1971 "cover up" job and rescued the chandelier. In 1982, he gave it back to the Zeiterion.

And Miss Harriet Rantoul, worth seeing twice, always had a cheery word for the restoration workers.

Harriet again with WHALE agent John Bullard and a bevy of volunteers towards the end if Phase I.

Entertainer and Oscar winner Shirley Jones, backed by a 28-piece orchestra, opened the partially restored Zeiterion September 25, 1982 to a full house and great acclaim.

Phase I in the auditorium.

The opening night audience and the yet-to-be restored rear auditorium.Planning for Phase II began long before the April construction start as this document dated January 12 attests. This transmittal and drawing are for motorized disappearing footlights, and Phase II included a complete stage lighting package, including two xenon Trouper follow spots, a total of 78 dimmers, 150 stage lights, and a memory light console. Vendors included Kliegl, TTI, American Stage Lighting, and Colortran. A complete new sound system, specified by restoration assistant Michael Guy, was also purchased out-of-contract.

Additional out-of-contract stage drapes to complement the Phase I purchase were specified: a silver-grey midstage traveler with matching legs and border, a cyclorama, and side tabs. These specs and many others were voluntarily typed by Miss Sara Stuart (inset) at the production office of the Brooklyn Academy of Music where the Director of Restoration was employed when he wasn't in New Bedford.

Roger Brett, of Brett Theatrical, won the drapery bid for Phase II. Roger was also the author of the fine book about the theatres of Providence, "Temples of Illusion."

Additional out-of-contract stage drapes to complement the Phase I purchase were specified: a silver-grey midstage traveler with matching legs and border, a cyclorama, and side tabs. These specs and many others were voluntarily typed by Miss Sara Stuart (inset) at the production office of the Brooklyn Academy of Music where the Director of Restoration was employed when he wasn't in New Bedford.

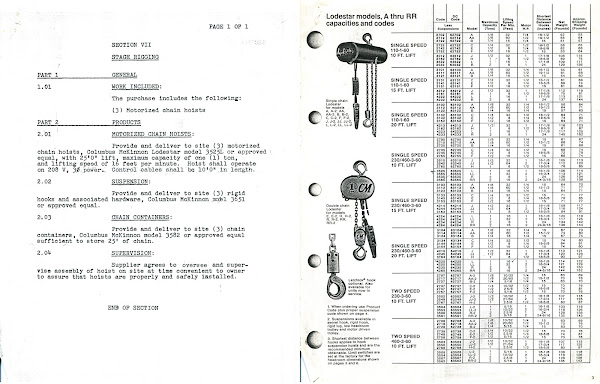

This out-of-contract spec was for three motorized hoists to lift the Voice of the Theatre motion picture loudspeaker cabinets up to the ceiling of the stage right wing when not in use, to clear the deck for stage shows.

Phase II construction drawings prepared by architect Joe Booth, consultants and engineers were completed January 25th, 1983 and sent out for bidding. The extensive Phase II work included completion of the auditorium; a new concession room to exactly match the adjacent lobby; expansion of stage support space; structural steel for the new 36-line counterweight headblock beam; the stage lighting upgrade previously mentioned; new substage dressing rooms; and complete HVAC, electrical and plumbing work.

Phase II construction drawings prepared by architect Joe Booth, consultants and engineers were completed January 25th, 1983 and sent out for bidding. The extensive Phase II work included completion of the auditorium; a new concession room to exactly match the adjacent lobby; expansion of stage support space; structural steel for the new 36-line counterweight headblock beam; the stage lighting upgrade previously mentioned; new substage dressing rooms; and complete HVAC, electrical and plumbing work.

The scaffolding supported an entire temporary floor for painting.

Painting from the temporary floor are contract men Oliver Pina and Robert Powers, filling in the filigree panels above the side wall muses. Numerous large and ugly circular air conditioning diffusers were removed and replaced by long horizontal spans completely concealed within the ceiling beams and designed by outstanding mechanical engineer "Tiny" Monjeau.

Drawing of all the auditorium surfaces were meticulously marked up by architect Joe Booth for plaster repair.Contract plasterers worked beneath the staging to prep the side walls for painting, Jim Leal shown here.

Down in the susbtage, contract electricians Albert Weigel (left) and James Jones again struggled to meet the deadline for re-opening.A glimpse of the electrical drawing for the above.

Connector strips for the stage lighting positions were modeled after 1920's Kliegl strips that repeated circuits across the stage and all but eliminated the need for jumper cables when hanging lights. A young local lighting designer was hired to design a repertory plot.

A picture of the memory lighting console. Enlarged ports in the projection booth made life easier for spot and board operators.

A detail drawing shows off Joe Booth drafting skills. No computer drafting was utilized on the Zeiterion job.

Drawing of all the auditorium surfaces were meticulously marked up by architect Joe Booth for plaster repair.Contract plasterers worked beneath the staging to prep the side walls for painting, Jim Leal shown here.

Down in the susbtage, contract electricians Albert Weigel (left) and James Jones again struggled to meet the deadline for re-opening.A glimpse of the electrical drawing for the above.

Connector strips for the stage lighting positions were modeled after 1920's Kliegl strips that repeated circuits across the stage and all but eliminated the need for jumper cables when hanging lights. A young local lighting designer was hired to design a repertory plot.

A picture of the memory lighting console. Enlarged ports in the projection booth made life easier for spot and board operators.

A view looking from the main lobby into the Phase II concession lobby. Joe Booth the architect transformed the concession lobby from an unadorned utilitarian rectangle into a duplicate of the 1923 main lobby. Joe Booth the volunteer designed and built the concession stand.

Gracious encouragement came from all corners in New Bedford, including WHALE board chair and grande dame Sarah Delano. Sarah, as she was known to one and all, provided housing for the Director of Restoration in the Wamsutta Club up the hill, and below is a note she wrote him.

Exciting news arrived that Massachusetts Governor Dukakis, in New Bedford to celebrate the one billionth golf ball made by Titleist, would also visit the Zeiterion.

A close inspection of this photograph reveals that the scaffolding had mostly been "struck" and stacked along the side walls.

Before the next day's Tommy Dorsey matinee, the Director of Restoration was paid a visit by his New York friends, Karen and Patti. Some Phase II construction was still ongoing, as evidenced by the "Gate B" construction sign next to the stage entrance.

A view from the bridge of the new counterweight system reveals that sub-contractor J.R. Clancy had completed installing only the bare minimum of rigging required by Tommy Dorsey. The system was specially designed by the Director of Restoration so that the flyman faced the stage.The Director of Restoration plays some Rossini on the concert grand as Karen, who worked for the Metropolitan Opera, appeared visibly impressed.

An institutional brochure printed soon after extolled the great beauty of the newly-restored theatre.

The main drape was now lit by a new valance borderlight as well as by the motorized footlights. As the house lights dimmed, the stage manager would press the backstage "footlights close" button, and instead of dimming out, the foots would slowly lower into the floor, with a lovely horizontal line of light traversing down the drape.

Exactly five (5) days later, the Zeiterion re-opened with the Tommy Dorsey Orchestra.

This is how it looked.

An institutional brochure printed soon after extolled the great beauty of the newly-restored theatre.

The main drape was now lit by a new valance borderlight as well as by the motorized footlights. As the house lights dimmed, the stage manager would press the backstage "footlights close" button, and instead of dimming out, the foots would slowly lower into the floor, with a lovely horizontal line of light traversing down the drape.

Joe Booth completely revamped the house right auditorium exit, shown above. Where previously the exit dumped out the back of the building, Joe relocated the exit doors to the side of the building, which allowed for a pass door to backstage; freed up space for a bona fide stage entrance with stage doorman room; and made room for a lockable onstage garage for the grand piano.

A view of the mural showing the concealed lighting units. "Box boom" positions were similarly concealed.

The Meyers loudspeakers for the new stereo sound system were likewise hidden from view in the old act announcer cabinets which had been rebuilt offsite.Except for new carpeting and a new exterior vertical sign, the Zeiterion was finished.Very soon thereafter, the Zeiterion stage was put through its paces by an unlikely team: two schoolteachers from New Bedford High. According to the Director of Restoration,"When I saw their 1983 production of 'Jesus Christ Superstar' I immediately realized that only Armand Marchand and George Charbonneau knew how to show off the Zieterion's fully-equipped stage to its best advantage." Their productions continue to grace that stage forty years later.

In 1990, the Zeiterion board recognized Joe Booth for "his talent, continued outstanding personal commitment, and leadership in the preservation of he Zeiterion."

This essay is dedicated to the scores of volunteers who worked their hearts out and their fingers to the bone to bring the Zeiterion back to life.

###

For a master index of all photo-essays, click here.

March, 2024

.jpg)

.jpg)

%20ZEITERION%20&%20JOE%20BOOTH%20&%20BOB%20FOREMAN%20%20.jpg)

%20ZEITERION%20&%20JOE%20BOOTH%20&%20BOB%20FOREMAN%20%20.jpg)

%20ZEITERION%20&%20JOE%20BOOTH%20&%20BOB%20FOREMAN%20%20.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

%20ZEITERION%20&%20JOE%20BOOTH%20&%20BOB%20FOREMAN%20&%20sara%20stuart.jpg)

%20ZEITERION%20&%20JOE%20BOOTH%20&%20BOB%20FOREMAN%20&%20ROGER%20BRETT.jpeg)

%20ZEITERION%20&%20JOE%20BOOTH%20&%20BOB%20FOREMAN.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)