This photo-essay should answer all pertinent questions about the preset pre-selective switchboards in three beautiful theatres, left to right, the Atlanta Fox, the Fox Oakland, and the Scranton Cultural Center at the Masonic Temple.

The Atlanta Fox switchboard (no longer in service) was manufactured by Hub Electric Company of Chicago, and contains 184 resistance dimmers operated by 120 handles, many loads requiring two or more mechanically linked faders located behind blank plates. The board also contains 240 pilot switch levers to operate remotely-located contacters, which when energized, provided juice to each circuit and allowed for pre-setting. Presetting was for switching only: dimmers could not be electrically preset.

The profile shot:

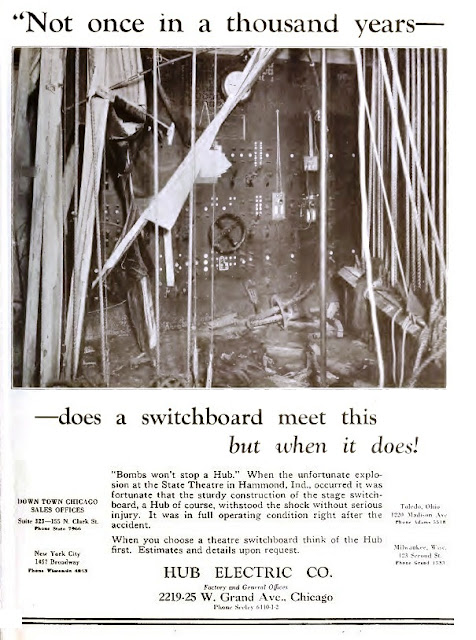

The Fox board was given the lead page in the 1930 Hub catalog.

The houses served by these boards had a fixed light plot, and the primary lighting unit was the borderlight. At the Atlanta Fox (below) three-hundred and sixty 300-watt lamps, glass-framed in four colors, gave the stage a warm and inviting glow. There were also twenty-eight front lights, forty side lights and a double-row buried cyc footlight, not to mention three super-bright arc follow spots. Burning in the (not visible) cyc border are two of the three lamps per border circuited to worklights.

In 1926 Hub joined "the largest board in the world" competition, its entry at the LA Shrine Auditorium, which has a 100-foot wide proscenium opening. This board was 26 feet wide, and the controls allowed for all borderlights to be split into "Center" and sides, so that the stage could be trimmed down to fifty feet. The borderlights themselves flew on two battens, center and sides, respectively. Behind the board face can be seen the Ward-Leonard resistance plates, and to their left is one end of the magazine (fuse) panel.

All contactor panels were located the the basement directly below the switchboard. Here is a view of the Shrine contactor panel, both front and rear, showing the huge amounts of copper required by this layered power grid. These frames would be permanently configured in the field to ensure balanced loads among the three phases. For a PDF of the entire 1926 article, click here.

This man is demonstrating the not-yet-energized Shrine switchboard.

Six months later, no less an authority than the New York Times proclaimed the Hub switchboard built for the Roxy to be "the largest in the world." The New York Roxy board (below) was a yard wider than the Atlanta Fox board, whose width measures 19 foot, eight inches. Nevertheless, these devices were considered to be "the last word" in compact dimmer board construction.

The resistance plates, open to the rear of the board, were wired on the neutral side of the circuit, as was all control wiring within the board. Below, wireman at Hub's factory make sense of the asbestos leads for the Roxy board. The terminals at the top connected to the contactor panel in the basement, which in turn connected to the fuse magazine panel, which connected to the theatre's lighting circuits.

The "Locke System," introduced in this ad from 1923, refers to Albert R. Locke, Hub's chief designer and patent-holder.

A closer view of the above board, heralded in 1923 as both "the largest" and "most compact." The dimming section, interlocked with awkward and unsightly vertical rods, would soon be perfected.

Locke was a triple threat: he designed the circuitry; the special switches; and the machinery required to motivate the dimmer plates, shown here. When properly lubricated, all the parts moved effortlessly.

A view of a Color Master dimmer handle (a sub-master) into which individual dimmers (shown to its right) could interlock, and which itself could lock into either side of the Slow Motion Wheel, seen beneath it. Spinning the Slow Motion Wheel as fast as possible would give you a fifteen-count fade.

Locke's wiring schematic:And Locke's special switch, the electrically-held contactor, which allowed control remote from the stage pilot board.

An example of a typical Locke contactor, manufactured by the Sundh Electric Company. The house light contactor shown is activated by either of two hold-in coils, separately powered, one each for the two Master presets. Both coils could be energized simultaneously, without fear of backfeeding.

Below is the Atlanta Fox Hub switchboard shop drawing, with "Locke System" prominent in the title block. Click here for a PDF view.

Stage circuits were located on the onstage (left) side of the slow-motion wheel, and the houselights to its right. Click here to view a PDF.

A front-on view of the entire board.

The center section contained the main controls, located beyond the slow motion wheel.

The main controls. From left, the two white levers are the Stage Mains for presets A and B, and the toggle switch between them is for preset C. Adjacent are the Black Out switches (grand masters) for stage and house; the control for the Atlanta Fox special "auto-sunrise effect;" and the House Main levers.

Each individual control module (left) contained a pilot light powered by the contactor, and two levers. There were four named preset selections, but only two could be chosen at any one time. Each bank's color master levers allowed another level of control.

Extended Control was a rarely-used function, where, for instance, the entire stage section could be controlled by a single toggle switch within the scenery. Control module levers set to Independent were controlled only by the Main Black Out switches.

The load of all the many contactors necessitated Main contactors, in two groups of three, half for the house and half for the stage presets, shown below.

Because of limited space, three dozen stage light controls were located on the houselight side of the Fox board, so there were actually six presets available, plus independents.

This 1930 Hub catalog plan of a Presentation House (like the Fox) has been annotated with suggested preset assignments. For a clean PDF view, click here.

The Fox Oakland (1928) featured a Westinghouse five-scene preset board with genuine Westinghouse-style handles, later copied by Luxtrol on some package boards.

Like the Atlanta Fox Hub board, Fox Oakland was a catalog headliner in 1930.

The Fox was also featured in one of their rare print ads. That a "Multi-Pre-Set Switchboard" was a Westinghouse achievement is open to question.

A closer look at the entire Oakland board shows that this switchboard lacked a house light section.

Expert Bill Counter has told me that at least five West Coast houses had separate houselight boards located in their projection rooms. This Westinghouse board was installed in the booth of the Los Angeles Fox Wilshire, where the controls for DC booth current are seen to the left of the houselight dimmers.

Hub Electric built lights and boards exclusively; Frank Adam's bread and butter was fuse boxes; but Westinghouse manufactured almost everything. They made the light bulbs.

Westinghouse boards featured the most classy combination running light and illuminated sign.

Westinghouse appeared to hold the some of the same patents as Hub, or perhaps there was a pool-- who knows?

Someone brilliant preserved the no-longer-used Fox Oakland switchboard by relocating it into the theatre's bar, so it continues to serve a useful purpose.

Although it no longer has any control, it can still be touched.

The five separate switching presets were controlled by the toggle switches above the pilot lights.

One merely selected the scene (or scenes) the director wanted.

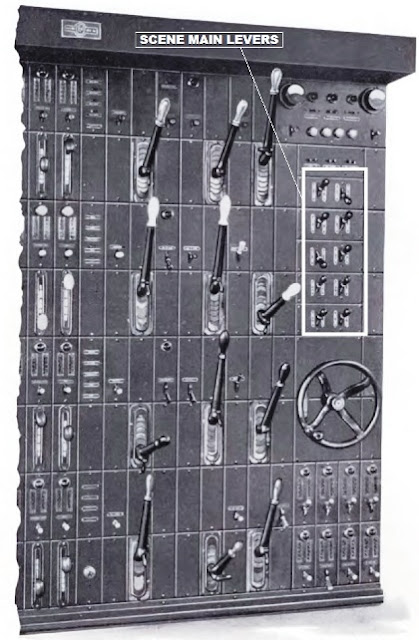

A catalog cut of the above:

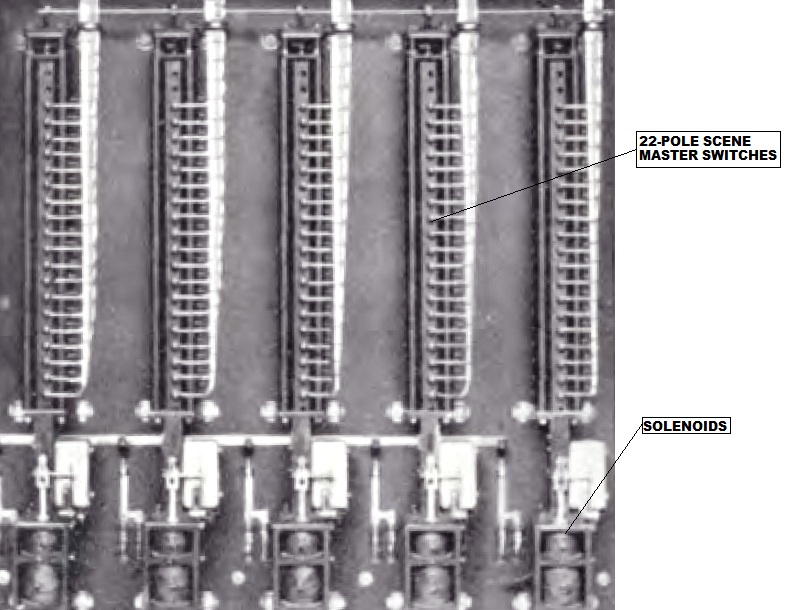

But the special patented switches were not the little toggle switches, but the maxi-multiple Scene Masters, located in the center. Unfortunately, at Oakland these switches have been removed.

From the patent drawing, this is what the Scene Master switches looked like from the side. The lever arm motivates a multi-pole cylindrical drum switch, the core bolted to the neutral bus.

The circled section of this catalog schematic shows these switches, in a three-scene board. To obviate backfeeding, each Main Switch had to contain as many poles as the board had dimmers, in this case, three.

In the patent documents, two 16-pole-plungers are illustrated. For a PDF view of the entire drawing, click here.

The Main Switches at the Oakland Fox board would have contained 74-pole-switches, and probably the largest switches ever built were 92-pole, in the Westinghouse board installed at the Barcelona Exposition of 1929.

Now we turn to the Scranton Cultural Center located in the Masonic Temple (1930) and designed by Raymond Hood, whose firm also contributed to the design of Radio City Music Hall two years later.

Art Deco like its home, the Temple's Frank Adam Ten-Scene All Master switchboard was tastefully finished in maroon. It is still in service, in a functioning theatre, no less!

Adam boards were available in designer colors, such as this example in the McAlester, Oklahoma Scottish Rite Temple, with a switch for magical motorized disappearing footlights.

A fair number of Frank Adam boards continue in service in Masonic temples, where the arcane lighting equipment and scenery hark back long before the 1920's. Here, a photo from Wendy Waszut-Barrett's wonderful book about the Santa Fe Temple, where the Adam board is located in the worst possible location, short of placing it on the upstage wall.

Functioning Frank Adam boards are not confined to Temples, however, as this shot from the Tampa Theatre shows.

Frank Adam was located not in Chicago or New York, but in St. Louis, Missouri.

The history of Frank Adam is easy to trace, because they loved to advertise and to instruct, as this 1921 ad reveals.

As far back as 1919, Adam had installed their new system in the People's Theatre in Chicago. Boards would soon be designed as "composite," meaning that the dimmers were set within the board, not atop it.

Adam's early boards did not include pre-setting, but pioneered the use of remotely controlled contactors. In their control module, the top lever energized the contactor, and the lower lever turned it off. By 1920, Hub employed the far less complicated electrically-held contactor.

A 1922 Frank Adam ad boasted of equipping Broadway, the Booth Theatre, which opened in 1913. Click here for PDF.

For many years, Frank Adam was associated with Major Equipment Company, of Chicago, who made lighting instruments. Together, they produced some lovely color catalog pages.

In 1922, Adam had not yet stumbled onto the secret of pre-set selective switching, but they knew what they were after. PDF view.

Finally in 1925 the breakthrough came, as displayed in the National Vaudeville Artists' Yearbook. The inset shows the "recent developments," the addition of Scene Master levers.

If you subscribed to the Chicago Engineering Works Review, you would have been among the first to learn that Frank Adam had installed the largest switchboard in the world in the Chicago Balaban & Katz' Uptown, opened in 1925.

According to the ballyhoo, this board was a staggering 28 feet long, as wide as a high school proscenium. The board was a "Ten Scene All Master Pre-selective" switchboard.

Two Adam contactor banks large and small, the left from the (no longer active) Warner's Hollywood and the Santa Fe Temple to the right. Frank Adam also patented their contactor, which was manufactured by Cutler-Hammer.

The ten scene board in the Detroit Masonic Temple:

To the right (onstage) side of the Ohio Theatre (Columbus) board was the stage section, main controls in center, and houselights to the far left. The controls in the bottom right were for DC stage arc light pockets, and the pushbutton stations along the onstage edge controlled the Peter Clark elevators. PDF view.

Instead of dedicated master handles for the houselight dimmers, the 1928 Warner's Hollywood featured a unique cross-mastering system, whereby any dimmer could be locked to submaster X or Y, and those subs could be locked into the hydraulically-assisted Grand Master Z. This board was a mere 17'6" wide.

The Hollywood board (like the Scranton, finished in maroon) illustrates well-calculated customized lighted signs.

On that same board, here are the ten Scene Main levers, situated to the right of the Grand Master dimmer handles and directly above the Slow Motion Wheel.

The Frank Adam patent drawings show only a wiring diagram of these "Westinghouse switches."

The excellent 1928 Frank Adam catalog includes a diagrammatic wiring scheme. Starting a the main neutral feeder (1), the control power path flowed through the Scene Main "All Master" switches (2), to the scene selector toggle switches (3), and thence to the contactor coil (4).

The rear side of a typical ten-scene board, where beyond a pair of steel doors one can see the Scene Master switches.

Here is a closeup view of the Scranton board, thanks to the efforts of photographer and theatre manager John Cardoni. To the left are the main neutral service feeders connecting to the board's main neutral bus. The many terminals shown tie to the large cable bundle, feeding control signal down to the contactor board in the basement. On the right are six of the Scene Masters, bolted to the neutral bus, because it was the custom to wire control on the neutral side. Directly below the plungers is the rear bearing for the Slow Motion Wheel.

And this is as close as you will ever get to an asbestos sheathed and laden fifty-four-pole cylindrical drum switch.

In rare installations where the Scene Main required multiple control locations, solenoids were utilized to motivate these switches, as seen below.

The largest Frank Adam Ten-scene is not known, but sixty-three-pole switches were required at the New York Paramount (1926).

In 1930, Frank Adam installed a board larger than their own (1925) "world's largest." For the Los Angeles Pantages, this monster measured twenty-seven feet wide, with 152 dimmers. It was a five-scene board.

The 1928 Frank Adam catalog sets the outer limit for Scene Main switches at 200-poles!

We are grateful to the folks who cherish and maintain these strange machines. This is how the Atlanta Fox, with assets of forty million dollars, treats their board.

Photo Credits:

Rick Zimmerman

John Cardoni

Wendy Waszut-Barrett, Historic Stage Services

Mitch Deutsch/Ray Spurlin

Bill Counter & Mike Hume (special thanks!)

Floyd Jillson

Lloyd Pearson

Janice McDonald

Internet

Theatre Historical Society

Thanks to Garry Motter, Bill Counter, Mike Hume, Wendy Barrett, and Rick Zimmerman.

For more on the Atlanta Fox switchboard, click here.

For more on Westinghouse boards, click here.

For more on Frank Adam boards, click here.

To view the 1928 Frank Adam catalog, click here.

For a master index of all photo-essays, click here.

November 2018