"The victims were splashed with blazing oil when a sheet of flame flashed through the transformer room into the coal vault, starting several small fires in the theatre basement and creating dense clouds of acrid smoke that repelled rescuers. The men had to make their own way to the upper floor, attempting with burlap bags to beat out the flames on each other's clothes as they did so." Below, the arrows trace the sole egress path to the street from the death chamber, across the width of the theatre building, which had to be navigated in the pitch black dark. Click to see a larger view.

"Twenty-four quarts of oil were splattered about the premises and began burning furiously, sending forth billows of murk. An alarm was sounded and fire apparatus responded. The cry of fire rang through the building, and the 175 men at work at various parts of the structure dashed for the street."

Below, a man surveys the aftermath from the vantage of the Page Street exit vestibule. "Of the five rushed to the Rhode Island Hospital, two were not expected to survive through the early morning. They were Antonio Dellorca, 34, and William Sinclair, 28. Neither had recovered consciousness late last night. Max Heymann, 40, Charles Merli, 42, and Marlio Guerci, 24, were given an even chance to live by hospital authorities. The sixth injured man was Ernest Perry, 42. [Sinclair died five days later; Heymann nine days; and Guerci, thirteen days after.] Hyman and Merli were carried from the building with their clothes still aflame. The other victims likewise were assisted out, their apparel either still either flaming or smoldering. At Rhode Island Hospital, the surgical staff was summoned by a general alarm. Priest were summoned from the Cathedral to attend Dellorca, Merli, and Guerci." To read the complete newspaper accounts from July 21 and 22, click here.

A view of the Main Foyer, facing east, showing the Page Street exit doors, to the right of the Grand Stair and above the Coal Vault.

The 11,000 volt Providence transformer which was built by the Westinghouse Electric and Manufacturing Company and installed by the Narragansett Electric Company reduced the incoming voltage to 208 volts three phase and fed the 3000 ampere main switch on the theatre's power panel. Below, transformers and switchgear installed in the 1926 New York Paramount Theatre which may be similar in appearance to the Providence installation.

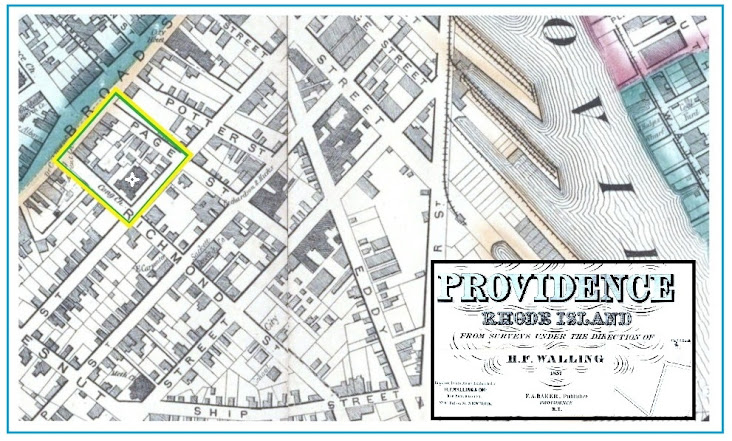

A bird's eye view of Providence showing (1) the Loew's State Theatre, (2) the Dyer Street substation from which the theatre was fed, and (3) the South Street (Main) power station of Narragansett Electric, both plants situated on the Providence River.

"A surge of voltage created by the explosion in the main generator plant of the Narragansett Electric Company (shown below) crippled the system, and deprived all Providence, East Providence, North Providence, Cranston, Bristol, Warren, Warwick, Johnston and even Narragansett Pier of electricity for light and power. Fumes generated by the flash in the main power plant rendered compartments in which the switches were located impenetrable, even with gas masks. Switches were torn from their fastenings, paint was burned from the walls, and the long copper busses carrying power were twisted like bands of elastic."

Initially, State Public Service Engineer Ralph Eaton blamed the explosions on a defect in the transformer which caused it to explode the second it was energized, but he was contradicted on Sunday.

This twenty second video on utube vividly illustrates untamed power of high voltage, the electrical arc preventing the disconnector switch from killing the power.

Loew's Incorporated (arrow below) owned and controlled MGM, and only MGM pictures were shown at Loew's Theatres. Not surprisingly, the top grossing film was Gone with the Wind, according to this fact-filled 1958 article "Loew's State Theatre is 30."

The face of Leo the MGM lion was woven into all the damask wall hangings, below. Every arch in the the foyers and auditorium was originally framed in plush velour, elevating Leo to an ermine-covered stature.

Marcus Loew is claimed to have said, "We sell tickets to theatres, not movies" and his chain rivaled Fox for the most elaborate picture palaces in the deluxe class. The Loew's State was designed by Rapp & Rapp, seated 3232, and was designed as a Presentation house with a combination policy of stage shows and movies. It was one of a dozen constructed as part of Loew's 1928 chain expansion plan, including the five "Wonder theatres" of New York and concluding in 1931 with the Loew's Triboro in Astoria, Queens.

The stage, a serviceable 28'-6" deep on the shallow side, was equipped with a Hub switchboard, a Peter Clark counterweight system and organ lift, and four additional Clark elevators which were added to the scope of the job during construction and are annotated on a Joe Booth 1985 drawing, below. On the upstage wall was a steel paint bridge, removed in 1978 to make way for additional system pipes, and completing the outlay was a substage screening ("cue") room. An HD view of the drawing below can be seen at this link, as well as the 1927 drawings, basement and main floor.

Despite this wealth of stage equipment, and unlike all other Loew houses in the circuit, the Providence theatre opened with neither orchestra nor vaudeville. Is it possible that Loew executives, still reeling from the loss of supervisor Max Heymann, got the heebie-jeebies and envisioned the place as a solemn shrine "devoid of the spectacular"?

Could the negligent factor involve the Vault door? Samuel Swan, Narragansett head, addressed the matter on the day of the explosions.

That the property was erected on consecrated ground was another theory, and indeed the Richmond Street Congregational Church (white star) had once occupied the southernmost corner of the land, as shown below in 1857. But over the years since 1905, the church itself had become the Bullock's theatre, one of the first film houses, as well as a circus, brewery, bowling alley and billiard parlor.

Besides Bullock's, there was another theatre on the Loew plot, the Gaiety, which stood on Weybosset Street where the theatre arcade would be constructed. Neither Bullocks's nor the Gaiety had ever been struck by lightning.

Five years later in 1933, at the bottom of the depression, Loew's finally capitulated to vaudeville, the band under the baton of Ken Whitmer, supplemented by organist Maurice Cook. The stage show policy lasted fifteen months, but Maurice played on until 1947.

1938 was a red letter year for the Loew's, with live appearances by MGM starlets Judy Garland and Freddie Bartholomew, and a hurricane in between. In February, Garland played four-a-day for a week, the first stage show since the house reverted to a film only policy in late 1934. Providence was the second stop on her month-long tour, which opened at Loew's State in Times Square.

On September 21, one-hundred mile-an-hour winds from a surprise hurricane caused a tidal wave to flood downtown Providence to thirteen feet above street level. For a closer view click here.

Both front and back basements of the Loew's were flooded from floor to ceiling, and dozens of motors submerged for days, such as for the organ blower, had to be removed and "baked" before they could run again. Fortunately, stagehands left the organ console elevator at the Top position (stage) and the console escaped undamaged. Following the storm, a new transformer was installed under the City-owned sidewalk and out of the theatre building entirely.

Half the orchestra seating and carpets were replaced, and the Loew's reopened $70,000 poorer ten days after. In November, MGM's British child star Freddie Bartholomew played the house, and that was the end of stage usage for nearly two decades. His name was still visible on the door to the star dressing room forty years later.

A repeat performance occurred on September l, 1954, but this time the organ console was at bottom and never played again, and Loew chose not repair the backstage motors, where the ground water level had permanently risen higher than the basement floors. At the other end of the building, the empty death chamber, three and one half feet below basement level, became a permanent black pool, containing no electricity whatsoever.

In August 1970, the house began its rapid downward descent with the advent of blaxploitation pictures (left) and similar fare and the Loew's State shuttered ten months later. Racetrack owner B.A. Dario and his wife Sylvia bought and ostensibly saved the theatre, but people worried because Dario had torn down the Albee (1919) the previous year. But almost immediately, they reopened as "The Dario Palace Theatre," later shortened to the Palace Theatre, and ran for four years. The Palace has attained cult status as a concert venue, a haven for hippies, with an occasional boxing match or film thrown in.

When the local and ingenious contractor Paul Kruger was hired to repair the dome six months later and temporarily removed the massive supply air duct from above it, he could find no structural defect that would have caused the fall-- no water damage or any other kind.

Why did Loew's order such a fancy rosette and not install a chandelier? In anticipation of it arrival, an iron hanging point had been installed in the attic, and already in place was a chandelier dimmer on the switchboard and seven circuits capable of juicing one hundred and fifty 75-watt Loew's Rose lamps. Was the chandelier, like the vaudeville, sacrificed as an offering? Were Loew executives afraid that the thing might crash, in the manner of "the Phantom" of three years before?

In 1975-76, the theatre went dark for six months while B.A. Dario spent a reputed $500,000 to renovate the house as "the Ocean State Theatre." Following a disastrous six-month try at showing first-run pictures, he closed the house. Fortunately, in July 1978, the former Loew's was purchased from Dario and legitimately saved by civic leaders, rechristened the "Ocean State Performing Arts Center." OSPAC premiered fifty years to the day after the original debut, on October 6, 1978, with Brian Jones All Tap Revue opening for Ethel Merman, live on stage-- and atop the newly repaired pit lift, thanks to the work of scores of volunteers.

The superficial Dario renovation had not touched the dank dungeons of the theatre, neither the boiler room complex beneath the lobby nor the substage. This photos give an idea of the devastation brought on by the increased ground water level: left is the newly dug drainage trench in the stage basement, with one of two new sump pump assemblies shown in the distance installed prior to dressing room reconstruction. Right is the organ blower which until the sump pumps were activated, sat in a pool of fetid black water three feet deep for twenty-five years, in a room much smaller and less scary than the death chamber up front, also water-filled.

A view of the York CO2 refrigeration plant at the Louisville Loew, identical to the Providence installation in the boiler room beneath the lobby. When the Providence water table rose after the 1938 flood, shallow trenches were dug to divert the ground water away from the machines.

Within a week of the 1978 announcement that the theatre was saved, during August when the theatre was dark, one quarter of the half-ton twelve-foot diameter ceiling dome rosette (below) plunged downward and landed dead center of the first row of the loge, its angle iron frame spearing and destroying the two best seats in the house.

When the local and ingenious contractor Paul Kruger was hired to repair the dome six months later and temporarily removed the massive supply air duct from above it, he could find no structural defect that would have caused the fall-- no water damage or any other kind.

Why did Loew's order such a fancy rosette and not install a chandelier? In anticipation of it arrival, an iron hanging point had been installed in the attic, and already in place was a chandelier dimmer on the switchboard and seven circuits capable of juicing one hundred and fifty 75-watt Loew's Rose lamps. Was the chandelier, like the vaudeville, sacrificed as an offering? Were Loew executives afraid that the thing might crash, in the manner of "the Phantom" of three years before?

Thanks in alphabetical order to: Laurie Amat, Joe Booth (Zeiterion architect), Lanham Bundy (Providence Public Library), Bill Counter, Liz Fields, Dalton Kurrle (Kennesaw Blueprint), Garry Motter, Ted Stevens (first general manager of PPAC), and Rick Zimmerman.

Interviews with: Roger Brett, author of Temples of Illusion; Paul Kruger, the contractor who repaired the rosette; James McCusker, Loew's State chief engineer, retired, the guy who said to me, "That's the death chamber."

Sources: Providence Journal archives, Cinema Treasures, and my 1981 285-page operating Manual for the theatre.

Managers at the Providence Performing Arts Center declined to comment for this article.

Author Bob Foreman and faithful assistant Joe Heelon, with the newly-functioning upstage lift (sans skirts), 1979.

For a master index of all photo-essays, click here.

12/25/2021